Lyme diagnosis and testing can be very confusing. This confusion has contributed to false positive diagnoses and unnecessary treatment.

As in other infections, typical testing for Lyme disease involves looking for antibodies produced by the body’s immune system in response to infection. This is called serologic testing because the antibodies are found in blood serum.

Testing positive for antibodies is called seropositive and testing negative for antibodies is called seronegative.

Notes about this article

As with most content on this site, this article is generally focused on testing in North America. It concentrates on serologic testing, which is useful for diagnosing and ruling out Lyme infections in the appropriate context.

Direct detection testing—such as PCR/DNA genetic testing and culture—has been used in the lab setting but is not recommended in general clinical practice.

For discussion of diagnosis of neurological Lyme disease (aka Lyme neuroborreliosis), please consult North American or German guidelines. A spinal tap to obtain a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may be useful to diagnose neurological Lyme disease involving the central nervous system (CNS). If the level of Lyme antibodies in CSF is substantially greater than the level of Lyme antibodies in blood serum, than this can confirm a diagnosis of neurological Lyme disease, which is treated with 2-3 weeks of antibiotics.

⭐ In depth commentary: Lyme neuroborreliosis: known knowns, known unknowns

Context is important

Exposure history

Lyme disease is caused by a very geographically restricted bacterial infection spread by Ixodes (aka blacklegged or deer) ticks. In North America, Borrelia Burgdorferi and rarely Borrelia mayonii cause Lyme disease. Europe has two additional major species: Borrelia Garinii and Borrelia afzelii, which may necessitate European-specific testing.

After a tick attaches, it takes time—typically 36-48 hours or more—for the bacteria to “wake up” and transmit to a human. Note: Transmission time may be lower in Europe.

In highly endemic areas like Connecticut and New York, studies have shown 2-3% of detected tick bites result in Lyme disease. Because of the low risk of transmission, post-exposure antibiotic prophylaxis against Lyme disease is only recommended for high risk bites.

Lyme disease is geographically and seasonally restricted for a number of reasons, including:

- Ixodes ticks only live in certain places.

- Since ticks are not born with Borrelia bacteria, they need to feed on an animal (e.g. mice) to become infected.

- In some places, the ticks have different behaviors, which cause them to usually not bite humans (to transmit) and infected animals (to become infected).

- Ticks are only active during certain times of the year, and this behavior varies geographically.

- A fraction of Ixodes ticks contain Borrelia bacteria, another factor that varies geographically.

- If a tick is an adult, it will often be big enough to be noticeable so that it can be removed before transmission can occur.

Avoid unnecessary and unscientific testing

As part of the admirable “Choosing Wisely” campaign to reduce unnecessary tests and treatments, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) warns:

Don’t test for Lyme disease as a cause of musculoskeletal symptoms without an exposure history and appropriate exam findings. [1]

The CDC [4], French Society of Internal Medicine, and other experts [22] around the world have expressed similar sentiments to the ACR.

The 2020 consensus Lyme disease guidelines emphasize that unnecessary testing can cause harm:

Indiscriminate testing may result in misattribution of symptoms to Lyme disease with potential delays in appropriate care and unnecessary antibiotic exposure.

As discussed in the CDC video below, determining the pretest probability of Lyme disease is very important:

⭐ More from CDC: Basic and advanced discussion of when to order Lyme disease testing

Lyme disease testing: Useful when performed appropriately

One known problem is that we can produce antibodies for years or decades after a Lyme infection has been eradicated. Therefore, a seropositive test on its own is not necessarily indicative of active infection.

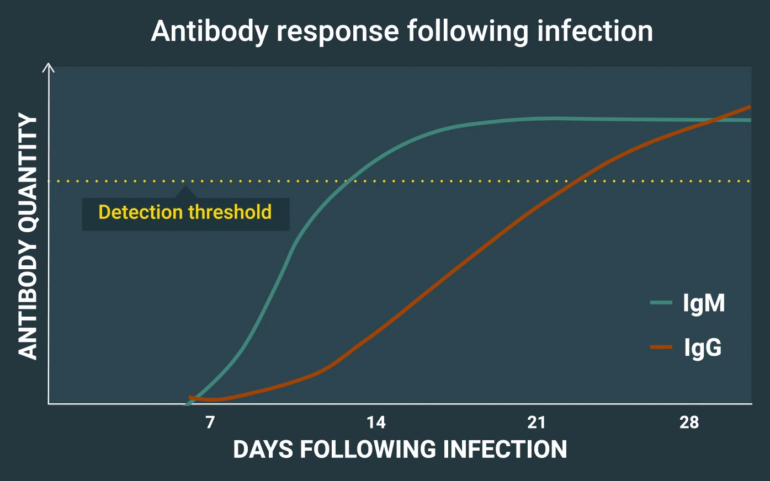

In addition, it can take a few weeks for detectable antibodies to build up in the body. This window period can be observed in other infections, like HIV. Pseudoscience advocates frequently mislead about Lyme antibody testing by failing to differentiate testing performance in early infection from testing performance in late infection.

Below is a CDC-produced illustrative example of antibody production in Lyme disease, which triggers a positive test once a detection threshold is reached.

Two types of antibodies are shown: IgG and IgM. Typically, a detectable IgM antibody response is produced first, followed by a detectable IgG response.

Some guidelines from CDC:

- Patients who have had Lyme disease for longer than 4-6 weeks, especially those with later stages of illness involving the brain or the joints, will almost always test positive.

- A patient who has been ill for months or years and has a negative test almost certainly does not have Lyme disease as the cause of their symptoms.

- Serologic testing is generally not useful or recommended for patients with single EM rashes. For this manifestation, a clinical diagnosis (alone) is recommended.

Since IgG antibodies are detectable after 4-6 weeks of infection, experts echoed CDC in concluding:

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) seronegativity in an untreated patient with months to years of symptoms essentially rules out the diagnosis of Lyme disease, barring laboratory error or a rare humoral immunodeficiency state.

Beware IgM false positives

IgM Lyme testing is notorious for producing false positive results, which is why it is only used in very limited circumstances, i.e. during the first 30 days of illness before detectable IgG antibodies would be produced in the event of a Lyme infection.

The CDC diagnosis and testing page states:

Positive IgM results should be disregarded if the patient has been ill for more than 30 days.

A CDC Lyme FAQ addressed how to interpret long-lasting symptoms where an IgG test was negative but the IgM test was positive:

If you have been infected for longer than 4 to 6 weeks and the IgG Western Blot is still negative, it is highly likely that the IgM result is incorrect (e.g., a false positive). This does not mean that you are not ill, but it does suggest that the cause of illness is something other than the Lyme disease bacterium.

Experts agree around the world

A strong scientific consensus is evident about Lyme disease diagnosis and testing, based on decades of scientific research.

A 2018 French review of 16 Lyme diagnostic guidelines from 7 countries “revealed a global consensus regarding diagnosis at each stage of the infection.” The only outlier was the pseudoscience group German Borreliosis Society (Deutsche Borreliose-Gesellschaft, DBG), a German counterpart to the pseudoscience group ILADS.

Independent studies show testing accuracy in late stage

A 2016 systematic review [8] that included 8 studies of CDC-recommended two tier test performance in “Late Lyme” showed Lyme antibody testing to be 99.4% sensitive and 99.3% specific** in North America.

In other words, out of 100 people with Late Lyme disease, 99-100 of them will test positive. Out of 100 people who may believe they have Late Lyme disease but do not, 99-100 of them will test negative.

Misinformation can convince patients to ignore or misinterpret negative tests to justify a false “Chronic Lyme” diagnosis.

Predatory labs: How they trick people

Experts strongly warn against unvalidated testing [5, 9]. Quackwatch [10] and Science-Based Medicine [11] both provide accessible explanations about the differences between validated, science-based tests and unvalidated tests.

In North America, only CDC-recommended and FDA-cleared or approved testing should be used. Health agencies in Canada make the same recommendations as CDC.

Sadly, a number of predatory labs exploit permissive laws surrounding “lab developed tests” to peddle testing that should not be relied upon.

Some predatory labs boast that they are CLIA-certified, but such lab certification does not mean that a test is useful. Even the notoriously fraudulent lab Theranos was CLIA certified.

CDC scientists explain:

- CLIA certification of a laboratory indicates that the laboratory meets a set of basic quality standards.

- It is important to note, however, that the CLIA program does not address the clinical validity of a specific test (i.e., the accuracy with which the test identifies, measures, or predicts the presence or absence of a clinical condition in a patient).

- FDA clearance/approval of a test, on the other hand, provides assurance that the test itself has adequate analytical and clinical validation and is safe and effective.

Besides misrepresenting CLIA certification, predatory labs use other methods to trick patients, including:

- Charging big bucks,

- Testing for many biomarkers to maximize the chance of a non-negative result,

- Creating proprietary diagnostic criteria, and

- Returning indeterminate results, which will often be interpreted as positive.

How can high prices trick people? There is a well-established principal in psychology whereby we tend to rely on price as a marker of quality.

Science-based Lyme testing is generally covered by insurers and health systems, and is low-cost regardless. A CDC analysis of 2014-2016 costs found that Lyme testing was, on average, $42 for the first tier screening test (median: $34). If the second tier confirmatory test was necessary, the cost averaged $65 (median: $33) for each of the two tests (IgM + IgG).

Testing from predatory labs can cost much more than mainstream science-based tests, which can mislead people into thinking they are somehow superior.

Perils of proprietary protocols

Some predatory labs use variants of mainstream tests but sell a proprietary interpretation. CDC has warned against this practice:

If a laboratory uses “in-house” criteria for interpretation of FDA-cleared tests for Lyme disease, this indicates the laboratory has modified the test and the clinical validity and safety is not certain.

In the video below, infectious disease expert David Patrick, MD describes how unvalidated testing—that we consider to be predatory—became so popular and why it can cause terrible consequences.

Patrick discusses the danger of “in house” diagnostic criteria by citing data produced by long-time quackademic Brian Fallon, MD with funding by Lyme pseudoscience groups. Fallon sent samples from 40 healthy patients to a “Lyme specialty laboratory”.

According to IgeneX criteria, 23 of the 40 submitted samples (57.5%) might be considered positive. Using a hypothetical population with 1% Lyme disease prevalence, if 57.5% of people had falsely positive tests, 98% of positive tests would be false positive.

In 2023, a new assessment of IgeneX criteria confirmed what Fallon’s data revealed: IgeneX criteria should not be relied upon.

See also:

- NIH discusses IgeneX unreliability for Lyme testing

- FDA cites IgeneX for problematic testing (explains how the 98% number was calculated)

How Lyme antibody testing works

Antibody testing for Lyme disease requires two different tests to establish a positive result. If either the first tier test or the second tier test is negative, the test result is negative overall.

But in the event of a negative result, Dr. Adriana Marques of the NIH states:

For patients with signs or symptoms consistent with Lyme disease for less than or equal to 30 days, the provider may treat the patient and follow up with testing of convalescent-phase serum.

The first tier of the “two-tiered testing” system is an Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA aka ELISA).

The second tier of the well-established Standard Two-Tiered Testing (STTT) involves IgM and IgG Western Blot tests, which can be complicated to understand. The Western Blot is also called an immunoblot or a line blot.

Newer tests FDA-cleared and CDC-recommended!

In 2019, CDC added a second test system to its recommended tests, the Modified Two-Tiered Test (MTTT). In the MTTT, the second tier is a different ELISA that is FDA-cleared specifically for the MTTT.

By using the MTTT, testing is simpler, costs may be reduced, and Lyme disease is more likely to be detected in the first weeks of infection.

A drawback of the MTTT is that potentially useful information is no longer determined about which types of antibodies are being produced by the body.

See also:

- Lyme testing algorithm flow charts by Dr. Adriana Marques

- Lyme testing interpretation guide by Association of Public Health Laboratories

More about Western Blot testing in North America

The IgG Western Blot test is designed to detect antibodies specific to Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria that cause Lyme disease. For Lyme disease in North America, a positive IgG Western Blot test requires at least 5 of 10 measured “bands” to be positive (or reactive).

The scored IgG bands are 18 kDa, 24 kDa (OspC)†, 28 kDa, 30 kDa, 39 kDa (BmpA), 41 kDa flagellin (Fla), 45 kDa, 58 kDa (not GroEL), 66 kDa, and 93 kDa.

The Lyme IgM Western Blot test measures 3 different types of antibodies. The North American IgM Western Blot is considered positive only if 2 of 3 IgM bands are positive (or reactive).

The scored IgM bands are 24 kDa (OspC)†, 39 kDa (BmpA), and 41 kDa (Fla).

As noted above, the IgM Western Blot should only be used in the first 30 days of illness.

† According to CDC, “Depending upon the assay, OspC could be indicated by a band of 21, 22, 23, 24 or 25 kDA.”

Important: Don’t misinterpret a negative test as positive

Many people without Lyme disease will test positive for some bands. Therefore, CDC has cautioned:

It is not correct to interpret a test result that has only some bands that are positive as being “mildly” or “somewhat” positive for Lyme disease.

For example, in one study, 43% of healthy people and 75% of syphilis patients tested positive for IgG band 41. In a study of US veterans in New York, 76% of those without Lyme disease tested positive for IgG band 41. In a 1996 study, in healthy people, 55% and 21% tested positive for IgG band 41 and IgM band 41, respectively.

Another study found that is was quite common for healthy people to test positive on the 66 kDa band.

Even without a Borrelia burgdorferi infection, many of us produce antibodies that will react on a Lyme test. Notably, harmless bacteria found naturally in our mouths can cause us to test positive for band 41.

Both tiers are important

A positive Lyme antibody test requires both tiers to be positive (or equivocal in some tests) as many without Lyme infections can test positive on single tests. For example, one study found up to 40% of patients with Lupus and other rheumatic diseases test positive on the first tier ELISA test. The second tier test is necessary to stop a false positive diagnosis.

The American Society for Microbiology recommends against ordering the Western blot without a positive ELISA screening:

The Lyme immunoblot test is designed only as a confirmatory test, so it is important not to test screen-negative samples.

LymeScience recommends against:

- Tests from any of the following labs or lab-associated entities: IgeneX, DNA Connexions, Galaxy Diagnostics, Medical Diagnostic Laboratories (MDL), Milford Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory, Advanced Lab, Fry Laboratories, Ceres Nanosciences (Nanotrap), Global Lyme Diagnostics, Pharmasan Labs (iSpot Lyme), Coppe Laboratories (myLymeTest), ArminLabs, i-Labs (successor to Infectolab Americas, Infectolab, BCA-Clinic, and BCA-lab), Australian Biologics, Melisa Labs, Moleculera Labs (Cunningham Panel), R.E.D. Labs, Immunosciences Lab, Aperiomics, Te?ted Oy (Tezted Limited, TICKPLEX, note misconduct from Tezted founders), Lyme Diagnostics Ltd. (DualDur cell technology), ProGene (DX Genie), Ionica Sciences (IonLyme), T Lab Inc. (TLab), Veramarx, Vibrant America/Vibrant Wellness, Research Genetic Cancer Centre (RGCC)/Biocentaur (PaLDiSPOT, PrimeSpot), Deutsches Chroniker Labor (B16+ test), Nordic Laboratories, IncellDX, Dedimed GmbH Europarc Labor (AK-18Save), IgeneX-associated Acudart Health, Alianza Biohealth, Rupa Health (part of Fullscript), Universal Diagnostic Laboratory, Mosaic Diagnostics (formerly Great Plains Laboratory)

- Any lab on Quackwatch’s list of “Laboratories Doing Nonstandard Laboratory Tests“

- CD57 testing

- Diagnosis with microscopy, e.g. Live Blood Cell Analysis or dark field microscopy.

- Urine tests

- electrodermal devices that use skin conductance or impedance like Meridian Stress Assessment (MSA) and ZYTO, Visual Contrast Sensitivity testing (VCS))

- Lymphocyte Transformation Test (LTT)

- ELISpot and interferon gamma tests (Also LymeSpot and other assays based on T-cell activity)

- MELISA testing

- Visual Contrast Sensitivity testing (VCS)

- IgA antibody tests [50]

- Western immunoblots on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or any serology on CSF other than for calculating the CSF:serum antibody index [39]

- Phelix Phage tests

- Circulating immune complexes (in Poland, KKI or Krążące kompleksy immunologiczne)

- European testing in the absence of exposure to European Ixodes ticks

- Failing to follow testing strategies recommended by CDC or local infectious diseases organizations

- Failing to perform and acknowledge both tests of the established two-tiered test

- Using testing that is not cleared or approved by the FDA

- Clinical diagnosis without a science-based rationale

- Diagnosis via a questionnaire of non-specific symptoms

- including discredited checklists by Joseph Burrascano and Richard Horowitz (HMQ Horowitz MSIDS Questionnaire)

- Diagnosis from an unscientific practitioner, including those who market themselves using the following terminology: Lyme literate (especially those affiliated with ILADS), integrative, functional, alternative, complementary, Traditional Chinese Medicine, holistic, natural, Biological, Ayurvedic, chiropractic, naprapathic, homeopathic, and naturopathic

- Diagnosis via magical beliefs, for example from a psychic, energy healer, shaman, or practitioner of muscle testing (aka ART-Autonomic Response Testing or applied kinesiology)

- Direct-to-consumer testing that hasn’t been ordered by a medical provider (e.g. LetsGetChecked and Everlywell)

- Relying on Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certification as an indication that a test result is legitimate (see CDC discussion)

- Relying on tick testing to make treatment decisions

- Any testing not recommended by CDC

Additionally, LymeScience endorses guidance by the Association of Public Health Laboratories, which is in line with other experts and referenced on the CDC Lyme diagnosis and testing site:

Scenarios for which Lyme disease serologic testing is NOT recommended include:

- Presence of erythema migrans in high incidence areas.

- Absence of likely Ixodes tick exposure (CDC: Regions Where Ticks Live)

- Lack of travel to, or residence in, a Lyme disease endemic area (CDC: Lyme Disease Maps).

- Following completion of one or more antibiotic course(s) for Lyme disease:

- Testing should not be used to monitor response to therapy or determine ‘cure.’

- Pressure from patient or patient representatives in the absence of clinical criteria supporting risk for Lyme disease infection.

Experts from the American College of Rheumatology, American Academy of Neurology, and Infectious Diseases Society of America also recommend against† routine Lyme testing for people with various non-Lyme conditions such as:

- Asymptomatic person following a tick bite

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

- Parkinson’s disease

- Dementia or cognitive decline

- New onset seizures

- Psychiatric illness

- Developmental or behavioral disorders of children

- Chronic cardiomyopathy of unknown cause

† list via Wormser et al

See also the following LymeScience pages:

- How chronic Lyme recruits followers

- Lyme misdiagnosis illustrated

- Red flags of chronic Lyme quackery

- CDC scientist: Why bands 31 and 34 aren’t used to test for Lyme disease

- When do symptoms mean Lyme disease?

- UK warns about inappropriate Lyme disease testing

Other misconceptions about Lyme disease diagnosis and testing are discussed below.

Common Misconceptions About Lyme Disease

Table excerpted and reformatted*** from the longer 2013 paper (ref 2 below, which is worth reading):

False negatives

Misconception: “Blood tests are unreliable with many negatives in patients who really have Lyme disease.”

Science: Just as with all antibody-based testing, these are often negative very early before the antibody response develops (<4-6 weeks). They are rarely if ever negative in later disease.

Isolated IgM seropositivity

Misconception: “Patients with many months of symptoms may have only a positive IgM Western blot.”

Science: Because the IgG response develops in 4-6 weeks, patients with symptoms of longer duration than this should be IgG positive; isolated IgM bands in such patients are almost always a false positive.

Seropositivity after treatment

Misconception: “Positive blood tests after treatment mean more treatment is needed.”

Science: After any infection resolves, the immune system continues to produce specific antibodies for an extended period. This is not an indication of persistent infection.

Antibiotics effect on serologic tests

Misconception: “Antibiotics make blood tests negative during treatment”

Science: There is no evidence that this happens and no biologic reason it would.

The clinical diagnosis of Lyme disease

Misconception: “Lyme disease is a clinical diagnosis that should be made based on a list of symptoms.”

Science: No clinical features, except erythema migrans or possibly bilateral facial nerve palsy—in the appropriate context—provide sufficient specificity or positive predictive value. Laboratory confirmation is essential except with erythema migrans.

Persisting fatigue & cognitive symptoms in isolation as evidence of brain infection

Misconception: “Patients with fatigue and memory difficulties have Borrelia burgdorferi infection of the brain.”

Science: These symptoms are not specific for B. burgdorferi infection and only rarely are evidence of a brain disorder.

Severity of Lyme disease

Misconception: “B. burgdorferi infection is potentially lethal.”

Science: Although Lyme disease can cause heart or brain abnormalities, there have been remarkably few—if any—deaths attributable to this infection.

LymeScience note: After this paper was published, CDC published[3] three case studies of deaths associated with Lyme carditis, though two patients had preexisting heart conditions. While it’s not entirely clear if the infection caused the deaths, CDC still reiterates, “Prompt recognition and early, appropriate therapy for Lyme disease is essential.”

Prolonged treatment

Misconception: “If, following treatment, symptoms persist, or serologic testing remains positive, additional treatment is required.”

Science: Multiple well-performed studies demonstrate that recommended treatment courses cure this infection. Retreatment is necessary occasionally, but not frequently.

Symptomatic improvement on antibiotics as validation of the diagnosis

Misconception: “Rapid symptomatic improvement on treatment proves the diagnosis despite negative blood tests.”

Science: Non-microbicidal effects of antibiotics may result in symptomatic improvement. In controlled trials, 1 patient in 3 improved in response to placebo.

Bottom Line

There is substantial evidence supporting the accuracy of FDA-cleared tests once antibodies build up in the body (4-6 weeks post-infection).

The CDC concurs:

You may have heard that the blood test for Lyme disease is correctly positive only 65% of the time or less. This is misleading information. As with serologic tests for other infectious diseases, the accuracy of the test depends upon the stage of disease. During the first few weeks of infection, such as when a patient has an erythema migrans rash, the test is expected to be negative.

Several weeks after infection, currently available ELISA, EIA and IFA tests and two-tier testing have very good sensitivity.

It is possible for someone who was infected with Lyme disease to test negative because:

- Some people who receive antibiotics (e.g., doxycycline) early in disease (within the first few weeks after tick bite) may not develop antibodies or may only develop them at levels too low to be detected by the test.

- Antibodies against Lyme disease bacteria usually take a few weeks to develop, so tests performed before this time may be negative even if the person is infected. In this case, if the person is retested a few weeks later, they should have a positive test if they have Lyme disease. It is not until 4 to 6 weeks have passed that the test is likely to be positive. This does not mean that the test is bad, only that it needs to be used correctly. [7]

** 99.4% sensitive (95% confidence interval: 95.7–99.9) and 99.3% (95% confidence interval: 98.5-99.7%) specific.

*** LymeScience reformatted the table and added punctuation, emphasis, a note, and changed the word “evidence” to “science”. Excerpted for educational and commentary purposes.

Resources

1. Choosing Wisely: American College of Rheumatology

2. Halperin JJ, Baker P, Wormser GP. Common misconceptions about Lyme disease. Am J Med. 2013 Mar;126(3):264.e1-7.

3. CDC: Three Sudden Cardiac Deaths Associated with Lyme Carditis — United States, November 2012–July 2013

4. CDC: Lyme disease: Diagnosis and Testing

5. CDC: Lyme disease: Laboratory tests that are not recommended

6. CDC scientist Barbara J.B. Johnson, PhD: Book chapter of “Lyme disease: An Evidence-Based Approach”: Laboratory Diagnostic Testing for Borrelia burgdorferi Infection

7. CDC: “I have heard that the diagnostic tests that CDC recommends are not very accurate. Can I be treated based on my symptoms or do I need to use a different test?” Lyme FAQ.

8. Waddell LA, et al. The Accuracy of Diagnostic Tests for Lyme Disease in Humans, A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of North American Research. PLoS ONE. 2016.

9. CDC: Notice to Readers: Caution Regarding Testing for Lyme Disease

10. Quackwatch: Some Notes on Nonstandard Lyme Disease Tests

11. Science-Based Medicine: Lemons and Lyme: Bogus tests and dangerous treatments of the Lyme-literati

12. American Lyme Disease Foundation: Antibody-Based Diagnostic Tests for Lyme Disease

13. Botman E, et al. Diagnostic behaviour of general practitioners when suspecting Lyme disease: a database study from 2010-2015. BMC Fam Pract. 2018.

14. Article about “ELISpot” Lyme tests: New test has no added value in Lyme disease of the central nervous system

15. Duerden BI. Unorthodox and unvalidated laboratory tests in the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis and in relation to medically unexplained symptoms. Department of Health, London, UK, 2006.

16. CDC Q and A: Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Lyme Disease

17. Choosing Wisely: Lyme Disease

18. Gregson D, et al. Lyme disease: How reliable are serologic results? CMAJ. 2015.

19. Marques AR. Laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease: advances and challenges. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015.

20. RIVM (Netherlands): Lab tests alone not conclusive for diagnosis of Lyme disease

21. Eldin C, et al. Review of European and American guidelines for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Med Mal Infect. 2018;

22. Dessau RB, et al. To test or not to test? Laboratory support for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: a position paper of ESGBOR, the ESCMID study group for Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(2):118-124.

23. Science-Based Medicine: Experts slam CAM lab tests, call for better regulation

24. Dessau RB, et al. The lymphocyte transformation test for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis has currently not been shown to be clinically useful. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014.

25. Lyme Disease Testing: A Regulatory ‘Wild West’

26. Aguero-rosenfeld ME, Wormser GP. Lyme disease: diagnostic issues and controversies. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015.

27. A Patient-centered Guide to Lyme Disease Testing

28. Peiffer-smadja N, et al. The French Society of Internal Medicine’s Top-5 List of Recommendations: a National Web-Based Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2019.

29. Raffetin A, et al. Unconventional diagnostic tests for Lyme borreliosis: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;

30. Moore A, et al. Current Guidelines, Common Clinical Pitfalls, and Future Directions for Laboratory Diagnosis of Lyme Disease, United States. Emerging Infect Dis. 2016.

31. Mead P, et al. Updated CDC Recommendation for Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019.

32. Marques AR. Revisiting the Lyme Disease Serodiagnostic Algorithm: the Momentum Gathers. J Clin Microbiol. 2018.

33. Debiasi RL. A concise critical analysis of serologic testing for the diagnosis of lyme disease. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014.

34. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. A systematic literature review on the diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for Lyme borreliosis. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016.

35. Van gorkom T, et al. Prospective comparison of two enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assays for the diagnosis of Lyme neuroborreliosis. [ELISpot, LymeSpot] Clin Exp Immunol. 2019.

36. Theel ES, et al. Limitations and Confusing Aspects of Diagnostic Testing for Neurologic Lyme Disease in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2019.

37. John TM, Taege AJ. Appropriate laboratory testing in Lyme disease. Cleve Clin J Med. 2019.

38. Ramsey AH, et al. Appropriateness of Lyme disease serologic testing. Ann Fam Med. 2004.

39. Infectious Diseases Society of America, American Academy of Neurology, and American College of Rheumatology: 2020 guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme disease.

40. Public Health Wales Observatory: Is there any evidence that testing for Lyme disease using the IGENEX or ARMINLABS facilities is superior to what is available in the UK?

41. Association of Public Health Laboratories: Suggested Reporting Language, Interpretation and Guidance Regarding Lyme Disease Serologic Test Results

42. Jones SL, et al. Laboratory tests commonly used in complementary and alternative medicine: a review of the evidence. Ann Clin Biochem. 2019.

43. Marques AR, et al. Comparison of Lyme Disease in the United States and Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2021.

44. Andany N, et al. A 35-year-old man with a positive Lyme test result from a private laboratory. CMAJ. 2015.

45. Morshed M, et al. Epidemiology of Lyme disease and pitfalls in diagnostics: What practitioners need to know. BCMJ. 2022.

46. Consumer Reports, American College of Rheumatology, ABIM Foundation: Tests for Lyme disease: When you need them—and when you don’t (PDF) (Pruebas para la Enfermedad de Lyme Cuándo las necesita y cuándo no)

47. Ružić-Sabljić E. [Pitfalls and Benefits of Serological Diagnosis of Lyme Borreliosis From a Laboratory Perspective.] Croatian Journal of Infection. 2021.

48. Melia MT, et al. Lyme disease: authentic imitator or wishful imitation? JAMA Neurol. 2014

49. American Lyme Disease Foundation: Antibody-Based Diagnostic Tests for Lyme Disease. 2017.

50. Theel ES. The Past, Present, and (Possible) Future of Serologic Testing for Lyme Disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2016

51. Branda JA, Steere AC. Laboratory Diagnosis of Lyme Borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2021.

52. Lohr B, et al. Laboratory diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: Current state of the art and future perspectives. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2018.

53. Markowicz M, et al. Testing patients with non-specific symptoms for antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato does not provide useful clinical information about their aetiology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015.

54. Önal U, et al. Is there a role for dark field microscopy in the diagnosis of Lyme disease? A narrative review. Infect Dis Clin Microbiol. 2023.

55. Miller M, et al. Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2024 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2024.

56. Grąźlewska W, Holec-Gąsior L. Antibody Cross-Reactivity in Serodiagnosis of Lyme Disease. Antibodies (Basel). 2023.

57. Holmes DT. Self-Ordering Laboratory Testing: Limitations When a Physician Is not Part of the Model. Clin Lab Med. 2020.

58. Summer G, et al. LTT-Validity in diagnosis and therapeutical decision making of neuroborreliosis: a prospective dual-centre study. Infection. 2024. [Lymphocyte Transformation Test]

59. Theel ES, Pritt BS. The false promise of cellular tests for Lyme borreliosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022.

60. Baarsma ME, et al. Diagnostic parameters of cellular tests for Lyme borreliosis in Europe (VICTORY study): a case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022.

61. Halperin JJ, et al. Lyme neuroborreliosis: known knowns, known unknowns. Brain. 2022.

Studies on inappropriate testing

Al-Sharif B, Hall MC. Lyme disease testing in children in an endemic area. WMJ. 2011.

Ley C, et al. The use of serologic tests for Lyme disease in a prepaid health plan in California. JAMA. 1994.

Vreugdenhil TM, et al. Serological testing for Lyme Borreliosis in general practice: A qualitative study among Dutch general practitioners. Eur J Gen Pract. 2020.

Barclay SS, et al. Misdiagnosis of late-onset Lyme arthritis by inappropriate use of Borrelia burgdorferi immunoblot testing with synovial fluid. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012.

Ramsey AH, et al. Appropriateness of Lyme disease serologic testing. Ann Fam Med. 2004.

Conant JL, et al. Lyme Disease Testing in a High-Incidence State: Clinician Knowledge and Patterns. Am J Clin Pathol. 2018.

Porwancher R, et al. Immunoblot Criteria for Diagnosis of Lyme Disease: A Comparison of CDC Criteria to Alternative Interpretive Approaches. Pathogens. 2023.

Dessau RB, et al. Utilization of serology for the diagnosis of suspected Lyme borreliosis in Denmark: survey of patients seen in general practice. BMC Infect Dis. 2010.

Guérin M, et al. Lyme borreliosis diagnosis: state of the art of improvements and innovations. BMC Microbiol. 2023.

Shih P, et al. Direct-to-consumer tests advertised online in Australia and their implications for medical overuse: systematic online review and a typology of clinical utility. BMJ Open. 2023.

Yigit M, et al. Lyme serology in non-endemic countries: Why do we request it and what do we find? BMC Infect Dis. 2024.

Lakos A, et al. The positive predictive value of Borrelia burgdorferi serology in the light of symptoms of patients sent to an outpatient service for tick-borne diseases. Inflamm Res. 2010. (mirror)

Haselow D, Wendelboe A. How Prevalence Influences the Interpretation of Lyme Disease Test Results in a High-Incidence State (Wisconsin) Versus a Low-Incidence State (Arkansas). Zoonoses. 2025.

Kon E, et al. Lyme Disease Confirmatory Western Blot Is Redundant for Screen Negative Samples in Low Endemic Areas, British Columbia, Canada. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2024. [mirror]

Johansson M, et al. Deficiencies in communication between clinical microbiological laboratories and physicians may impair the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: A study of the use and application of serology in three neighbouring counties in Sweden. PLoS One. 2025.

Strizova Z. Seroprevalence of Borrelia IgM and IgG Antibodies in Healthy Individuals: A Caution Against Serology Misinterpretations and Unnecessary Antibiotic Treatments. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases.

2020.

Updated December 30, 2025