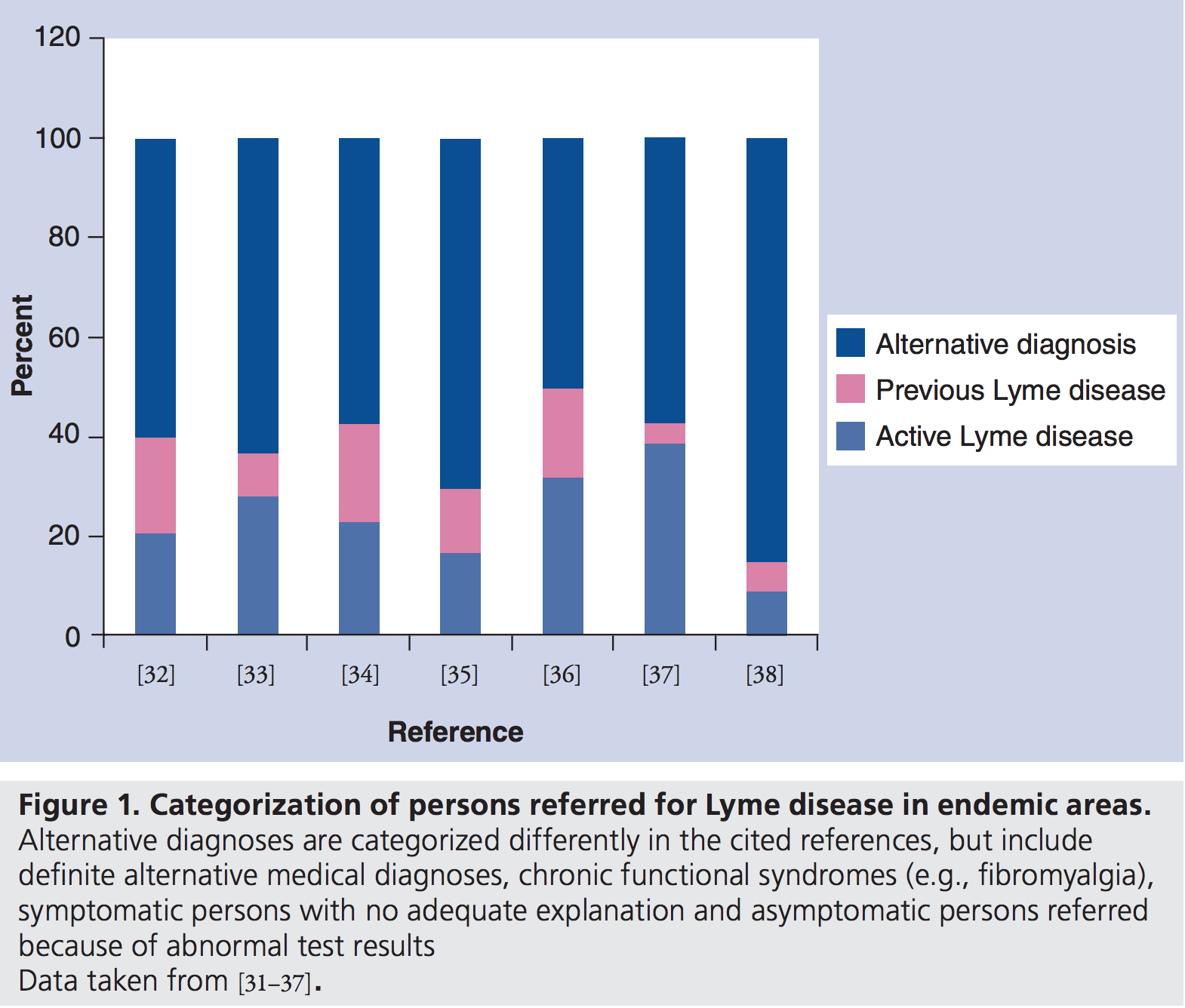

“In seven studies conducted in endemic areas, comprising a total of 1902 patients referred for suspected Lyme disease, only 7–31% had active Lyme disease and 5–20% had previous Lyme disease. Among the remainder, 50–88% had no evidence of ever having had Lyme disease.”

Source: Lantos, Paul “Chronic Lyme disease: the controversies and the science” Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 9(7), 787–797 (2011)

So what is causing the symptoms of “chronic Lyme” patients?

The CDC and NIH emphasize that experts do not support the use of the term “chronic Lyme disease” because of confusion. Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, 31 doctors and scientists classified those with the chronic Lyme label into four predominant groups:

- Category 1: Symptoms of unknown cause, with no evidence of Borrelia burgdorferi infection

- Category 2: A well-defined illness unrelated to B. burgdorferi infection

- Category 3: Symptoms of unknown cause, with antibodies against B. burgdorferi but no history of objective clinical findings that are consistent with Lyme disease

- Category 4: Post–Lyme disease syndrome

Feder et al observed “Only patients with category 4 disease have post–Lyme disease symptoms.” Looking at references 31-33 below, Feder et al stated:

Data from studies of patients who underwent reevaluation at academic medical centers suggest that the majority of patients presumed to have chronic Lyme disease have category 1 or 2 disease.

In other words, evidence indicates that the symptoms of most “chronic Lyme” patients were clearly not caused by Lyme disease. In addition, most “chronic Lyme” stories contain a number of red flags of quackery, including multiple false diagnoses.

References pointing to a massive problem of false positive diagnosis of Lyme disease:

- LymeScience: How chronic Lyme recruits followers

- 🇺🇸 Marzec NS, et al. Serious Bacterial Infections Acquired During Treatment of Patients Given a Diagnosis of Chronic Lyme Disease – United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(23):607-609. [press coverage]

- 🇺🇸 Fallon BA, et al. A comparison of lyme disease serologic test results from 4 laboratories in patients with persistent symptoms after antibiotic treatment. 2014.

- 🇫🇷 Hansmann Y, et al. Feedback on difficulties raised by the interpretation of serological tests for the diagnosis of Lyme disease. Med Mal Infect. 2014.

- 🇬🇧 Cottle LE, et al. Lyme disease in a British referral clinic. QJM. 2012. [LymeScience discussion and infographic]

- 🇨🇦 Patrick DM, et al. Lyme Disease Diagnosed by Alternative Methods: A Phenotype Similar to That of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2015.

- 🇦🇺 LymeScience: Australia has no Lyme disease- So why are activists promoting it?

- 🇳🇱 New test has no added value in Lyme disease of the central nervous system

- 🇺🇸 🧒 Ettestad PJ, et al. Biliary complications in the treatment of unsubstantiated Lyme disease. J Infect Dis. 1995.

- 🇺🇸 Wormser GP, Shapiro ED. Implications of Gender in Chronic Lyme Disease. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009.

- 🇺🇸 Role of Psychiatric Comorbidity in Chronic Lyme Disease

- 🇺🇸 Neoplasms Misdiagnosed as “Chronic Lyme Disease”

- 🇺🇸 Serious Bacterial Infections Acquired During Treatment of Patients Given a Diagnosis of Chronic Lyme Disease — United States

- 🇺🇸 Barclay SS, et al. Misdiagnosis of late-onset Lyme arthritis by inappropriate use of Borrelia burgdorferi immunoblot testing with synovial fluid. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012.

- 🇺🇸 NIH: Chronic Lyme disease

- 🇺🇸 CDC: Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (and Dangers of long-term or alternative treatments for Lyme disease)

- 🇺🇸 Medscape: Lyme Culture Test Causes Uproar

- 🇫🇷 Jacquet C, et al. Multidisciplinary management of patients presenting with Lyme disease suspicion. Med Mal Infect. 2018.

- 🇫🇷 Haddad E, et al. Holistic approach in patients with presumed Lyme borreliosis leads to less than 10% of confirmation and more than 80% of antibiotics failure. Clin Infect Dis. 2018. [Français, commentary]

- 🇫🇷 Voitey M, et al. Functional signs in patients consulting for presumed Lyme borreliosis. Med Mal Infect. 2019;

- 🇫🇷 Haddad E, Caumes E. Experience of three French centers in the management of more than 1,000 patients consulting for presumed Lyme Borreliosis. Med Mal Infect. 2019.

- 🇺🇸 CDC: Notes from the Field: Reference Laboratory Investigation of Patients with Clinically Diagnosed Lyme Disease and Babesiosis – Indiana, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018.

- 🇦🇹 Markowicz M, et al. Testing patients with non-specific symptoms for antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato does not provide useful clinical information about their aetiology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015.

- 🇨🇦 Gasmi S, et al. Practices of Lyme disease diagnosis and treatment by general practitioners in Quebec, 2008-2015. BMC Fam Pract. 2017.

- 🇳🇴 Roaldsnes E, et al. Lyme neuroborreliosis in cases of non-specific neurological symptoms. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2017..

- 🇳🇱 Zomer TP, et al. Non-specific symptoms in adult patients referred to a Lyme centre. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018.

- 🇳🇱 🧒 Zomer TP, et al. Nonspecific Symptoms in Children Referred to a Lyme Borreliosis Center. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020.

- 🇳🇱 Zwerink M. Predictive value of Borrelia burgdorferi IgG antibody levels in patients referred to a tertiary Lyme centre. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017.

- 🇳🇱 Nijman G, et al. Antibiotic treatment in patients that present with solely non-specific symptoms and positive serology at a Lyme centre. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;

- 🇺🇸 Kwit NA, et al. Notes from the Field: High Volume of Lyme Disease Laboratory Reporting in a Low-Incidence State — Arkansas, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017.

- 🇫🇷 Bouiller K, et al. Consultation for presumed Lyme borreliosis: the need for a multidisciplinary management. Clin Infect Dis. 2018.

- 🇺🇸 Lantos PM, et al. Poor Positive Predictive Value of Lyme Disease Serologic Testing in an Area of Low Disease Incidence. Clin Infect Dis. 2015.

- 🇩🇪 Csallner G, et al. Patients with “organically unexplained symptoms” presenting to a borreliosis clinic: clinical and psychobehavioral characteristics and quality of life. Psychosomatics. 2013.

- 🇺🇸 Tseng YJ, et al. Incidence and Patterns of Extended-Course Antibiotic Therapy in Patients Evaluated for Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2015. (commentary)

- 🇺🇸 Nelson RE, et al. Evaluation of serological testing for Lyme disease in Military Health System beneficiaries in Germany, 2013-2017. MSMR. 2019.

- 🇳🇱 Coumou J, et al. Ticking the right boxes: classification of patients suspected of Lyme borreliosis at an academic referral center in the Netherlands. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015.

- 🇸🇪 Svenungsson B, Lindh G. Lyme borreliosis–an overdiagnosed disease? Infection. 1997.

- 🇵🇱 Moniuszko A. The problem of overreporting and overdiagnosing Lyme disease in Poland. ECCMID 2018 Abstract. 2018.

- 🇺🇸 Molloy PJ, et al. False-positive results of PCR testing for Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2001.

- 🇳🇴 Ljøstad U, Mygland Å. The phenomenon of ‘chronic Lyme’; an observational study. Eur J Neurol. 2012. [paper mirror]

- 🇧🇷 De oliveira SV, et al. Lack of serological evidence for Lyme-like borreliosis in Brazil. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2018.

- 🇮🇹 🧒 Peri F, et al. Somatic symptom disorder should be suspected in children with alleged chronic Lyme disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2019. [excerpts]

- 🇺🇸 Fix AD, et al. Tick bites and Lyme disease in an endemic setting: problematic use of serologic testing and prophylactic antibiotic therapy. JAMA. 1998.

- 🇺🇸 Clayton JL, et al. Enhancing Lyme Disease Surveillance by Using Administrative Claims Data, Tennessee, USA. Emerging Infect Dis. 2015.

- 🇺🇸 Bashir M, et al. A Rare but Fascinating Disorder: Case Collection of Patients with Schnitzler Syndrome. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2018.

- 🇺🇸 Boyce RM, et al. Errors in diagnostic test use and interpretation contribute to the high number of Lyme disease referrals in a low-incidence state. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2020.

- 🇺🇸 Webber BJ, et al. Lyme Disease Overdiagnosis in a Large Healthcare System: A Population-based, Retrospective Study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019.

- 🇺🇸 Aguirre LE, et al. Anchoring Bias, Lyme Disease, and the Diagnosis Conundrum. Cureus. 2019.

- 🇺🇸 Lowry L, et al. Anchoring Bias on Lyme Disease Leading to Delayed Diagnoses. Mil Med. 2020.

- 🇫🇮 Kortela E, et al. Suspicion of Lyme borreliosis in patients referred to an infectious diseases clinic: what did the patients really have? Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2020.

- 🇩🇰 Gynthersen RM, et al. Classification of patients referred under suspicion of tick-borne diseases, Copenhagen, Denmark. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 2020.

- 🇩🇪 Hanses F, et al. Verdacht auf Borreliose – Was hat der Patient? [Suspected borreliosis – what’s behind it?]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2011.

- 🇮🇹 D’Alessandro R, et al. Tendency for overdiagnosis of neuroborreliosis. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1994.

- 🇳🇱 Blaauw AA, Bijlsma JW. Musculoskeletale klachten vaak ten onrechte aan Lyme-ziekte toegeschreven [Musculoskeletal symptoms often incorrectly attributed to Lyme disease]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1997.

- 🇺🇸 Sigal LH. Persisting complaints attributed to chronic Lyme disease: possible mechanisms and implications for management. Am J Med. 1994.

- 🇫🇷 Itani, Oula, et al. Focus on patients receiving long-term antimicrobial treatments for Lyme borreliosis: no Lyme but mostly mental disorders. Infectious Diseases Now. 2020.

- 🇫🇷 Bouilller, K, et. al. Presumed Lyme borreliosis: patients with confirmed Lyme borreliosis are less symptomatic than other patients [conference abstract]. 2019.

- 🇺🇸 Greco TP Jr, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with purported ‘chronic Lyme disease’. Lupus. 2011.

- 🇺🇸 Wormser GP, et al. Studies that report unexpected positive blood cultures for Lyme borrelia – are they valid? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017.

- 🇺🇸 McCarthy ML, et al. Lessons Learned from a Rhode Island Academic Out-Patient Lyme and Tick-Borne Disease Clinic. Rhode Island Medical Journal. 2020.

- 🇺🇸 Beeson AM, et al, 1428. Lyme Disease Treatment in the United States: Prescribing Patterns from a Nationwide Commercial Insurance Database, 2016-2018, Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2020.

- 🇫🇷 Guellec D, et al. Diagnostic impact of routine Lyme serology in recent-onset arthritis: results from the ESPOIR cohort. RMD Open. 2016.

- 🇺🇸 Hudman DA. Exposure to Ticks and their Pathogens in Northeast Missouri. Mo Med. 2018.

- 🇸🇪 Nilsson K, et al. A comprehensive clinical and laboratory evaluation of 224 patients with persistent symptoms attributed to presumed tick-bite exposure. PLoS One. 2021.

- 🇺🇸 Hsu VM, et al. “Chronic Lyme disease” as the incorrect diagnosis in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1993.

- 🇺🇸 🧒 Sigal LH, Patella SJ. Lyme arthritis as the incorrect diagnosis in pediatric and adolescent fibromyalgia. Pediatrics. 1992.

- 🇺🇸 Kaell AT, et al. Positive Lyme serology in subacute bacterial endocarditis. A study of four patients. JAMA. 1990.

- 🇦🇺 Schnall J. Characterising DSCATT: A case series of Australian patients with debilitating symptom complexes attributed to ticks. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021.

- 🇺🇸 Becker CB, Trock DH. Thyrotoxicosis resembles Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1991.

- 🇭🇺 Lakos A, et al. The positive predictive value of Borrelia burgdorferi serology in the light of symptoms of patients sent to an outpatient service for tick-borne diseases. Inflamm Res. 2010. (mirror)

- 🇺🇸 Marinopoulos SS, et al. Clinical problem-solving. More than meets the ear. N Engl J Med. 2010.

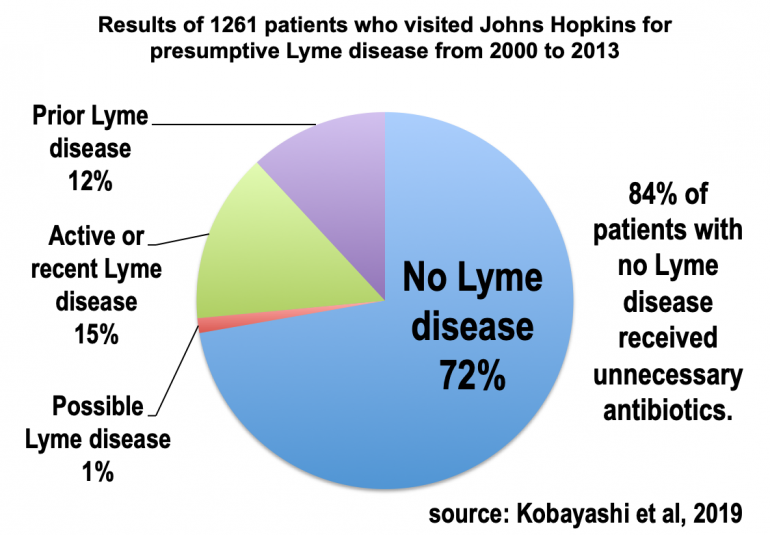

- 🇺🇸 Kobayashi, et al. Misdiagnosis of Lyme Disease with Unnecessary Antimicrobial Treatment Characterize Patients Referred to an Academic Infectious Diseases Clinic. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2019.

- 🇺🇸 Kobayashi, et al. Mistaken Identity: Many Diagnoses are Frequently Misattributed to Lyme Disease. American Journal of Medicine. 2021.

- 🇸🇰 Szep Z, Majtan J. Annular erythema as a cutaneous sign of recurrent ductal breast carcinoma, misdiagnosed as erythema chronicum migrans. Dermatol Online J. 2020.

- 🇺🇸 Lakraj A, et al. Uncertainty with a Twist of Lyme. Walsh Society Meeting, North American Neuro-ophthalmology Society Annual Meeting. 2017. (Abstract, Slides, Video)

- 🇺🇸 Shere-Wolfe KD, et al. Misdiagnosis of Lyme Disease in Patients Referred to an Academic Lyme Center. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2021.

- 🇺🇸 Feder HM Jr, Whitaker DL. Misdiagnosis of erythema migrans. Am J Med. 1995.

- 🇺🇸 🧒 Feder HM Jr, Hunt MS. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease in children. JAMA. 1995.

- 🇪🇸 Corral I, et al. Manifestaciones neurológicas en pacientes con serología positiva frente a Borrelia burgdorferi [Neurological manifestations in patients with sera positive for Borrelia burgdorferi]. Neurologia. 1997.

- 🇺🇸 Wormser GP. Documentation of a false positive Lyme disease serologic test in a patient with untreated Babesia microti infection carries implications for accurately determining the frequency of Lyme disease coinfections. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021.

- 🇺🇸 Boltri JM, et al. Patterns of Lyme disease diagnosis and treatment by family physicians in a southeastern state. J Community Health. 2002. [paper mirror]

- 🇫🇷 Raffetin A, et al. Multidisciplinary Management of Suspected Lyme Borreliosis: Clinical Features of 569 Patients, and Factors Associated with Recovery at 3 and 12 Months, a Prospective Cohort Study. Microorganisms. 2022. [earlier conference abstract]

- 🇫🇷 Sevestre J, et al. Emergence of Lyme Disease on the French Riviera, a Retrospective Survey. Frontiers in Medicine. 2022.

- 🇺🇸 Forrester JD, et al. Epidemiology of Lyme disease in low-incidence states. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015.

- 🇫🇷 Lutaud R, et al. When the patient is making the (wrong?) diagnosis: a biographical approach to patients consulting for presumed Lyme disease. Fam Pract. 2022.

- 🇳🇴 Aase A, et al. Validate or falsify: Lessons learned from a microscopy method claimed to be useful for detecting Borrelia and Babesia organisms in human blood. Infect Dis (Lond). 2016. [commentary]

- 🇺🇸 Butt OH, et al. A Case Report of Diffuse Ischemic Injury from Leptomeningeal Midline Glioma Metastases. Journal of Neurology and Neurological Disorders. 2021.

- 🇵🇱 Maksymowicz S, Siwek T. Diagnostic odyssey in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: diagnostic criteria and reality. Neurol Sci. 2023

- 🇺🇸 Ley C, et al. Lyme disease in northwestern coastal California. West J Med. 1994 Jun;160(6):534-9.

- 🇫🇷 Hamadou L, et al. Costs associated with informal health care pathway for patients with suspected Lyme borreliosis. Infectious Diseases Now. 2023.

- 🇬🇧 White B, et al. Management of suspected Lyme borreliosis: experience from an outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy service. QJM. 2013.

- 🇵🇱 Czupryna P, et al. Lyme disease in Poland – A serious problem? Adv Med Sci. 2016. [mirror, press discussion]

- 🇳🇱 van de Schoor FR, et al. Evaluation and 1-year follow-up of patients presenting at a Lyme borreliosis expertise centre: a prospective cohort study with validated questionnaires. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2024.

- 🇫🇷 Frahier H, et al. Characteristics of patients consulted for suspected Lyme neuroborreliosis in an endemic area. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2024.

- 🇹🇷 Yıldız AB, et al. Discrepancy between IDSA and ESGBOR in Lyme disease: Individual participant meta-analysis in Türkiye. Zoonoses Public Health. 2024.

- 🇺🇸 Aucott JN, Seifter A, Rebman AW. Probable late lyme disease: a variant manifestation of untreated Borrelia burgdorferi infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2012.

- 🇬🇧 Suliman F, et al. Most patients referred to a British infectious disease clinic with possible Lyme disease have a different final diagnosis: no change in the last decade [Conference abstract]. Escmid Global. 2024.

- 🇫🇷 Hamdad M. Patients adressés par leur medecin traitant pour suspicion de maladie de lyme au centre de compétence des maladies vectorielles à tiques (CCMVT) de la sarthe de septembre 2019 à Septembre 2020 : Quels sont les diagnostics retenus ? (Patients referred by their general practitioner for Lyme disease suspicion to the CCMVT (Center of Competence for Vector borne Tick-borne Diseases) of Sarthe from September 2019 to September 2020 : what are the established diagnoses ?). Thesis. Université Angers. 2021.

- 🇦🇷 Armitano RI, et al. Enfermedad de Lyme. Análisis crítico sobre su presencia en Argentina [Lyme’s disease. A critical analysis of its presence in Argentina]. Medicina (B Aires). 2024.

- 🇩🇪 Makarov C, et al. Early comorbidities and diagnostic challenges in people with multiple sclerosis with possible impact on disease management. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2025.

- 🇸🇮 🇺🇸 Ogrinc K, et al. Proportion of confirmed Lyme neuroborreliosis cases among adult patients with suspected early European Lyme neuroborreliosis. Infection. 2025.

- 🇫🇷 Caraux-Paz P, et al. Attention aux diagnostics associés chez les patients âgés suspectés de borréliose de Lyme : une étude multicentrique française. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses Formation. 2025. (Conference abstract)

- 🇫🇷 Balavoine AG, Patrat-Delon S. Accueillir les patients en errance médicale dans le contexte d’une suspicion de borréliose de Lyme : place d’une consultation couplée infectiologue/psychologue clinicien. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses Formation. 2025. (Conference abstract)

- Other references from Figure 1 are below

Inappropriate use of testing leads to false positive diagnosis

As discussed on the LymeScience testing and red flags of chronic Lyme quackery pages, there are many ways to receive a false positive Lyme disease diagnosis.

False positives are facilitated by predatory labs, discredited testing, and testing that has not been scientifically validated. But misinterpretation of conventional testing is also a problem. Examples include:

- Using the IgM Western blot test more than 30 days after the appearance of symptoms

- Why? In a true Lyme infection, IgG antibodies can usually be detected by 4-6 weeks. Plus other infections, such as Epstein-Barr virus, can cause a false positive.

- Ignoring or failing to perform the first tier ELISA test

- Why? The American Society for microbiology explains: “The Lyme immunoblot test is designed only as a confirmatory test, so it is important not to test screen-negative samples. Some antigens on the blot react with non-Lyme antibodies, and the immunoblot can be over-interpreted in the absence of a positive screening test.”

- Ignoring or failing to perform the second tier, confirmatory test

- Why? First tier ELISA testing can be falsely positive (or equivocal) for a number of reasons, including due to other infections or due to autoimmune diseases. In North America, Lyme disease testing is only validated if interpreted based on CDC and Health Canada recommendations.

- Misinterpreting fewer than 5 bands on the IgG Western blot as positive

- Why? Many people without Lyme disease will test positive for some bands, especially band 41, which is commonly positive in healthy people.

- Interpreting faint (but negative) Western blot bands as positive

- Note: Some predatory labs—such as IgeneX and Medical Diagnostic Laboratories (MDL)—return results that allow people to misinterpret indeterminate (IND) or faint bands as positive.

- Using non-standard Western blot bands such as bands 31 and 34

- Why? Using these bands has not been shown to improve testing. (more on bands 31 and 34)

- Using any non-standard “in-house” criteria for Western blot interpretation

- Why? CDC explains: “This indicates the laboratory has modified the test and the clinical validity and safety is not certain.”

- Misinterpreting persistent antibodies as persistent infection after a cured infection or asymptomatic infection that the immune system cleared on its own

- Why? Our immune systems have memories such that antibodies can be detected many years after infection.

According to the consensus of experts:

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) seronegativity in an untreated patient with months to years of symptoms essentially rules out the diagnosis of Lyme disease, barring laboratory error or a rare humoral immunodeficiency state.

References on false positive ELISA testing

- 🇧🇪 Keymeulen B, et al. False positive ELISA serologic test for Lyme borreliosis in patients with connective tissue diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 1993 Dec;12(4):526-8. (shareable link)

- 🇺🇸 Weiss NL, et al. False positive seroreactivity to Borrelia burgdorferi in systemic lupus erythematosus: the value of immunoblot analysis. Lupus. 1995 Apr;4(2):131-7.

- 🇺🇸 🧒 Sood SK, et al. Positive serology for Lyme borreliosis in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in a Lyme borreliosis endemic area: analysis by immunoblot. J Rheumatol. 1993 Apr;20(4):739-41.

References describing false positive IgM testing

- 🇨🇿 Strizova Z, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia IgM and IgG Antibodies in Healthy Individuals: A Caution Against Serology Misinterpretations and Unnecessary Antibiotic Treatments. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2020.

- 🇬🇧 Joyner G, et al. Introduction of IgM testing for the diagnosis of acute Lyme borreliosis: a study of the benefits, limitations and costs. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2022.

- 🇸🇪 Hillerdal H, Henningsson AJ. Serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis-is IgM in serum more harmful than helpful? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021.

- 🇳🇴 Ulvestad E, et al. Diagnostic and biological significance of anti-p41 IgM antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi. Scand J Immunol. 2001 Apr;53(4):416-21.

- 🇦🇹 Markowicz M, et al. Persistent Anti-Borrelia IgM Antibodies without Lyme Borreliosis in the Clinical and Immunological Context. Microbiol Spectr. 2021.

- 🇵🇱 Plewik D, et al. The presence of anti-EBV antibodies as the cause of false positive results in the diagnostics of Lyme borreliosis. Health Problems of Civilization. 2016.

- 🇺🇸 Seriburi V, et al. High frequency of false positive IgM immunoblots for Borrelia burgdorferi in clinical practice. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012.

- 🇺🇸 🧒 Lantos PM, et al. False Positive Lyme Disease IgM Immunoblots in Children. J Pediatr. 2016.

- 🇩🇪 Woelfle J, et al. False-positive serological tests for Lyme disease in facial palsy and varicella zoster meningo-encephalitis. Eur J Pediatr. 1998 Nov;157(11):953-4.

- 🇳🇴 Ulvestad E, Kristoffersen EK. Falskt positivt serologisk prøvesvar ved mistenkt borreliose [Translation from Norwegian: False positive serological test result in suspected Lyme disease]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2002 Jan 10;122(1):88-90.

- 🇺🇸 Garment AR, Demopoulos BP. False-positive seroreactivity to Borrelia burgdorferi in a patient with thyroiditis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010 Sep;14 Suppl 3:e373.

🧒 = Focusing on children and young people

References from Figure 1 :

31. 🇺🇸 Reid MC, et al. The consequences of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of Lyme disease: an observational study. Ann. Intern. Med. 128(5), 354–362 (1998). (mirror, Commentary: Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of Lyme disease leads to inappropriate health service use)

32. 🇺🇸 Sigal LH. Summary of the first 100 patients seen at a Lyme disease referral center. Am. J. Med. 88(6), 577–581 (1990).

33. 🇺🇸 Steere AC, et al. The overdiagnosis of Lyme disease. JAMA 269(14), 1812–1816 (1993).

34. 🇺🇸 Hassett AL, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and other psychological factors in patients with “chronic Lyme disease”. Am. J. Med. 122(9), 843–850 (2009).

35. 🇺🇸 🧒 Qureshi MZ, et al. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of Lyme disease in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 21(1), 12–14 (2002).

36. 🇺🇸 🧒 Rose CD, et al. The overdiagnosis of Lyme disease in children residing in an endemic area. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 33(11), 663–668 (1994).

37. 🇩🇪 Djukic M, et al. The diagnostic spectrum in patients with suspected chronic Lyme neuroborreliosis – the experience from one year of a university hospital’s Lyme neuroborreliosis outpatients clinic. Eur. J. Neurol. 18(4), 547–555 (2010).

38. 🇨🇦 Burdge DR, O’Hanlon DP. Experience at a referral center for patients with suspected Lyme disease in an area of nonendemicity: first 65 patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 16(4), 558–560 (1993)

Untreated Late Lyme Disease

In the United States, the typical manifestation of Lyme disease that is untreated for months or longer involves Lyme arthritis. In this stage, antibody tests are expected to be positive.

See also: LymeScience’s infographic on Lyme arthritis

According to Steere and Arvikar:

Patients with Lyme arthritis have intermittent or persistent attacks of joint swelling and pain in one or a few large joints, especially the knee, usually over a period of several years, without prominent systemic manifestations.

In Europe, a skin manifestation called acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans can occur in late stage Lyme infection.

References on Untreated Late Lyme

Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015.

Schoen RT. A case revealing the natural history of untreated Lyme disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011.

Brummitt SI, et al. Molecular Characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi from Case of Autochthonous Lyme Arthritis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014.

Washington Post: Medical Mysteries: Nurse solves mysterious ailment that puzzled orthopedists, oncologist

New York Times: My Son Got Lyme Disease. He’s Totally Fine

Hirsch AG, et al. Obstacles to diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease in the USA: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2018.

Steere AC, Schoen RT, Taylor E. The clinical evolution of Lyme arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 1987.

European specific

Mahieu R, et al. A 59-year-old woman with chronic skin lesions of the leg. (photo quiz and article) Clin Infect Dis. 2013.

Moniuszko-malinowska A, et al. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans: various faces of the late form of Lyme borreliosis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2018.

updated May 29, 2025