Like many health professionals, Dr. David Patrick, Director of the School of Population and Public Health at University of British Columbia, Canada, wanted to help patients who received a chronic Lyme diagnosis. So he and his colleagues studied the issue.

Similar to many other reports, the Canadian group found false positive Lyme diagnoses. In fact, all 13 chronic Lyme patients they looked at had no good evidence of having Lyme disease.

So what caused these false diagnoses? Significantly, all 13 patients had used a single alternative lab in the United States. The alternative lab had claimed a positive test result for 12 of the patients and a single positive band on a Western Blot for the remaining patient.

See also: LymeScience testing page– Predatory labs and how they trick people

The Canadian scientists found that the alternatively diagnosed chronic Lyme patients had striking similarities to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome patients. The researchers concluded that the chronic Lyme patients had “what is clearly a debilitating illness”, even though Lyme disease was not the cause.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is poorly understood and often includes Medically Unexplained Symptoms, which the UK NHS describe as follows:

Many people have persistent physical complaints, such as dizziness or pain, that don’t appear to be symptoms of a medical condition.

They are sometimes known as “medically unexplained symptoms” when they last for more than a few weeks, but doctors can’t find a problem with the body that may be the cause.

This doesn’t mean the symptoms are faked or “all in the head” – they’re real and can affect your ability to function properly.

Not understanding the cause can make them even more distressing and difficult to cope with.

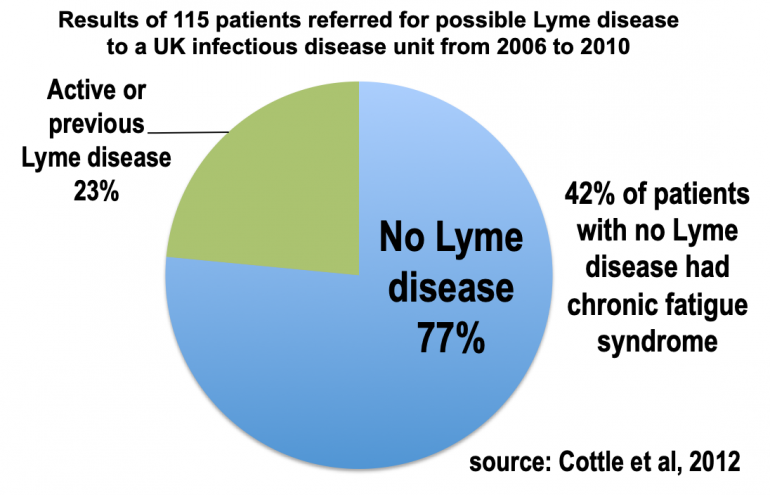

Dr. Lucy Cottle and colleagues published a UK-based study in 2012 that showed false positive Lyme diagnoses in patients referred for possible Lyme disease to the Tropical and Infectious Disease Unit (TIFU) at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital.

Only 23% (27) of the 115 patients had active or previous Lyme disease. Not only did most of the patients have no evidence of Lyme disease (past or present), but 42% (37) of those without Lyme disease had Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

Sadly, a number of the patients received false Lyme disease diagnoses. 40% (35) of the patients with no current or past Lyme disease had received Lyme disease treatments prior to consulting at the TIFU. Undoubtedly, patients did not get proper care for their true diagnoses.

The details of the patients who had visited non-NHS clinics were especially horrifying:

Twenty-six (23%) patients had consulted non-NHS clinics. All had chronic symptoms and 21 (81%) of them presented with fatigue. A total of 22 (85%) patients had received a diagnosis of LD and 9 of these 22 had also been diagnosed with co-infections such as babesiosis, bartonellosis, ‘cryptostrongylus’ infection, chlamydia or chronic candidiasis.

Diagnoses were based on unvalidated tests, such as direct or video-assisted light microscopy of blood, CD57 counts and immunological test panels performed overseas. Among 22, 15 also had Lyme serology performed in a reference laboratory, with a negative result in all cases. None of these 22 patients were considered to have LD at the TIDU, where 17 of them were diagnosed as having CFS.

Some details of anti-microbial regimens previously administered were available for 16 of the 22 patients with an unsubstantiated diagnosis of LD. These 16 patients had received at least 53 courses of antibiotics prescribed in non-NHS clinics, including at least 4 intravenous courses. Five patients had received five or more different anti-microbial agents and one had received eight different anti-microbials (Table 2). In some cases, antibiotic regimens were excessively prolonged, with up to 20 weeks of doxycycline in one instance.

The Cottle and Patrick studies are part of a well-established trend. In a comment on Patrick’s study, Dr. Alan Barbour noted that the phenomenon of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome being falsely blamed on Lyme disease has been seen since the late 1980s. He cited a 1990 study that found rampant false Lyme diagnoses and unnecessary antibiotics. The 1990 study concluded:

Anxiety about possible late manifestations of Lyme disease has made Lyme disease a “diagnosis of exclusion” in many endemic areas. Persistence of mild to moderate symptoms after adequate therapy and misdiagnosis of fibromyalgia and fatigue may incorrectly suggest persistence of infection, leading to further antibiotic therapy.

Attention to patient anxiety and increased awareness of these musculoskeletal problems after therapy should decrease unnecessary therapy of previously treated Lyme disease.

Dr. Barbour further commented:

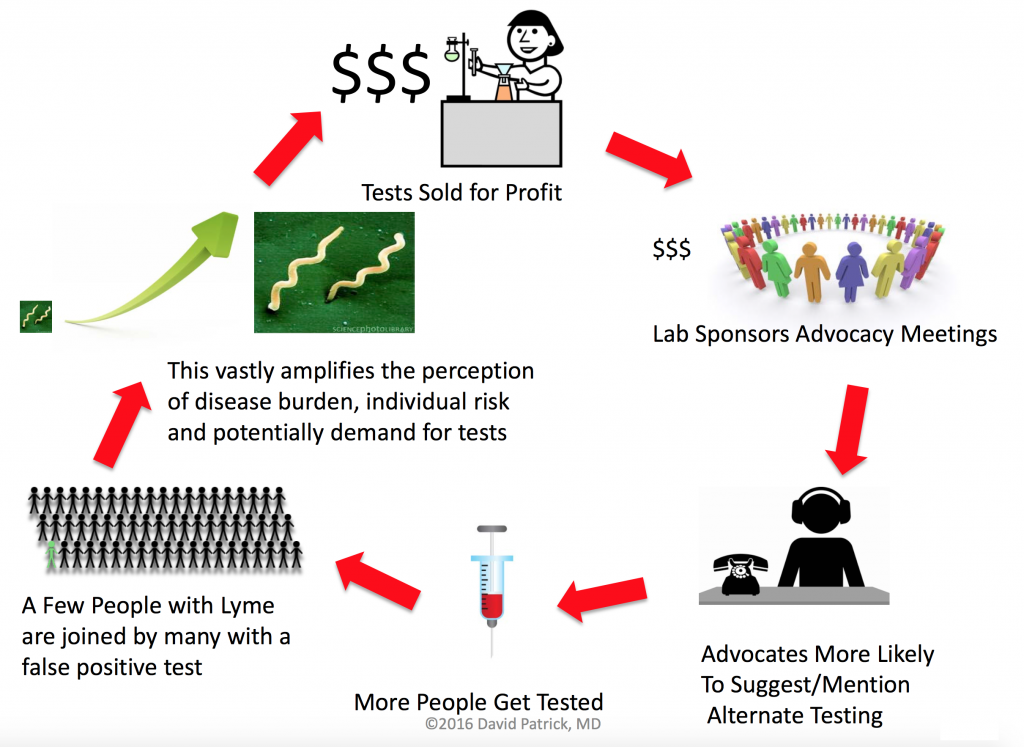

Given the choice between a diagnosis of CFS or, in other cases, fibromyalgia, for which there are limited treatment options, and LD, for which antibiotic therapy may promise a cure, is it any wonder that the diagnosis of LD is as common as it is and that “Lyme specialty” laboratories stay in business and, for all I know, prosper? Certainly, the authors are justified in their view that “individuals diagnosed with [alternatively diagnosed chronic Lyme syndrome] deserve comprehensive workup and care.”

However, an important unanswered question of the study is whether the alternatively diagnosed chronic Lyme syndrome patients changed their beliefs about whether they had LD or not? The fact is there has been insufficient progress over more than 3 decades in understanding what is as much a psychosocial and cultural phenomenon as a biological one.

Dr. Patrick also appeared on Global News (see video above) and presented a useful illustration of how chronic Lyme can spread socially. Other ways chronic Lyme spreads is via quacks and credulous media coverage.

An analysis from Australia (where there is no endemic Lyme disease) revealed “Almost 10% of respondents self-diagnosed after being exposed to a media report of Australian Lyme disease.”

Resources by Dr. Patrick:

- Explaining the mysteries of Lyme disease

- Video and Slides from a longer presentation on Alternatively Diagnosed Chronic Lyme Syndrome at the Conference to develop a federal framework on Lyme disease

- Q&A Tick Talk: What you need to know about Lyme disease

- Lyme Disease Diagnosed by Alternative Methods: A Phenotype Similar to That of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

- Lyme disease: How reliable are serologic results?

Other resources:

- Dr. Alan Barbour: “Lyme”: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome by Another Name?

- Dr. Harriet Hall: Does Everybody Have Chronic Lyme Disease? Does Anyone?

- LymeScience: More papers describing false Lyme diagnoses in CFS and fibromyalgia patients

- Cottle LE, et al. Lyme disease in a British referral clinic. QJM. 2012;105(6):537-43.

- UK NHS: Medically Unexplained Symptoms

- Dr. Steven Novella: Is Fibromyalgia Real?

- Dr. Alison Lai: Patients need answers. Doctors don’t always have them.