We came upon this 2023 conference presentation from doctors at a hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. They describe a woman who developed severe liver damage after being prescribed appalling drugs that are consistent with abuse by a chronic Lyme quack.

Real Lyme disease is easily treated with cheap, generic antibiotics.

All of the antibiotics prescribed to this woman are not recommended for Lyme disease. They are reflected on our list of red flags. A scientific review lists numerous non-recommended treatments:

- Long-term antibiotic therapy

- Multiple repeated courses of antibiotics for the same episode of Lyme borreliosis

- Combinations of antibiotics

- Pulsed dosing in which antibiotics are given on some days but not on other days

- First-generation cephalosporins, such as cephalexin, benzathine penicillin G, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, vancomycin, metronidazole [Flagyl], tinidazole, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [Bactrim], amantadine, ketolides, isoniazid, rifampin or fluconazole

- Drug therapy for babesiosis (that is, a malaria-like parasitic disease) or Bartonella spp. infection in the absence of evidence for active infection

- Hyperbaric oxygen, intravenous hydrogen peroxide or ozone therapy

- Energy-based or radiation-based therapies, such as ‘rife therapy’

- Nutritional therapies, such as burnt mugwort or glutathione

- Chelation and heavy-metal therapies

- Fever therapy

- Intravenous immunoglobulin

- Urotherapy (that is, the ingestion of one’s own urine)

- Apheresis

- Stem cell transplantation

- Drugs (such as cholestyramine), enemas, bee venom, various hormonal therapies (such as thyroid hormone), lithium orotate, olmesartan, naltrexone or bleach

Yes, doctors have to warn against all sorts of bizarre treatments, including bee stinging, enemas, and urine-drinking.

We highlighted drugs above that are in the report. Malarone (Atovaquone-Proguanil) and Artemisinin are anti-malarial drugs that are unrelated to Lyme disease. Malarone can be used for babesia but is not used for arthritis. CDC has reported on bogus babesiosis diagnoses facilitated by inappropriate testing. Cefdinir and minocycline are not in the consensus recommendations.

Vanishing Bile Duct Syndrome (VBDS): How Do Ducts Disappear?

Jose R. Russe, Joseph Cotton, Li Liu and Anurag Maheshwari, Institute for Digestive Health and Liver Disease at Mercy Medical Center

Background

Vanishing Bile Duct Syndrome (VBDS) is an acquired condition characterized by prolonged cholestasis and more than 50% progressive loss of bile ducts on liver biopsy (LBx). Common causes of VBDS are antibiotics (Abx) and herbal intake.

Reported cases of VBDS have been scarce, leading to a poorly understood pathophysiology thought to be immune-mediated cholangiolar damage in response to direct injury by drugs, metabolites, and prolonged stagnant bile salt exposure. We aim to provide evidence to clarify VBDS pathophysiology further.

Methods

A 63-year-old woman with recurrent Lyme arthritis was treated, in November, with Cefdinir (CFD), minocycline (MNC), and Flagyl (FLG) for ten days. A week later, her symptoms were unresolved, and she took Bactrim and Lamictal for five days.

Unfortunately, her symptoms continued, and she started Malarone and Artemisinins in addition to resuming CFD, MNC, and FLG. Finally, in February, she saw her provider for fatigue, nausea, constipation, pruritus, icterus, jaundice, and abdominal pain.

Results

Routine biochemistry (BCH) showed elevated liver enzymes (LFTs) and bilirubin (TB) of 4.9, and she was sent to the hospital (H), where new BCH showed an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 488 and TB of 11.

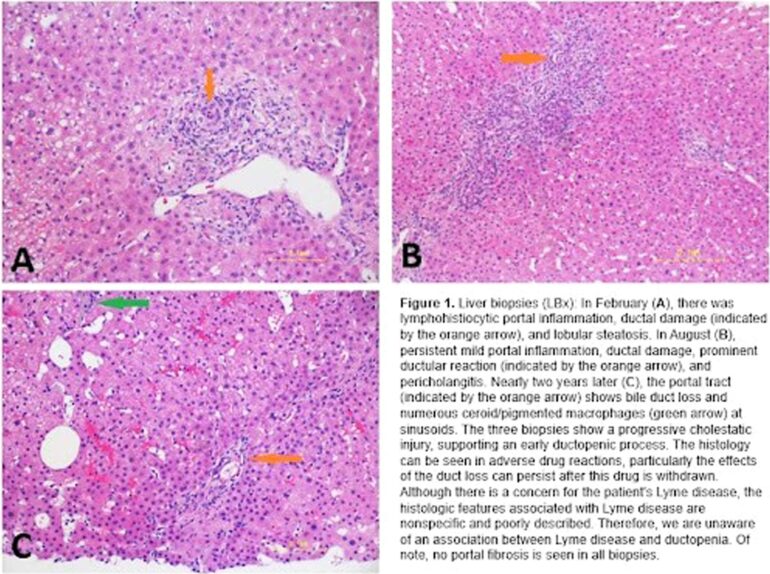

The ABx were stopped after a suspected drug-induced injury and started Ursodiol with tapered steroids. Imaging (IMG), autoimmune, and viral serology were all normal. She was discharged to a specialized liver clinic, where a LBx showed lymphohistiocytic portal inflammation and ductal damage (Figure 1A).

In March, her ALP was 515, TB was 32.1, and IMG showed hepatosteatosis, no obstruction, and cholestatic inflammation, resolved on repeat IMG in May. In August, ALP was 510, TB was 3.9, and repeat LBx showed persistent inflammation, worsened ductal damage, and pericholangitis (Figure 1B).

Nearly two years after stopping ABx, the LFTs were normal, except ALP was 341, and repeat LBx showed ductopenia with numerous sinusoidal macrophages (Figure 1C).

Conclusion

Progressive cholestatic injury supporting an early ductopenic process is seen in adverse drug reactions, particularly persistent ductal loss without portal fibrosis, despite withdrawing the offending drug (Figure 1).

Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that chronic T-cell-mediated cholestatic injury, bile duct destruction by circulating leukocytes, and hepatic repair and resolution by Kupffer cells, maintaining hepatic homeostasis, were the driving forces for the emergence of VBDS. The highlighted case and objective data provide evidence for the natural history of VBDS, prompting further research.

Figure 1

Image caption:

Figure 1. Liver biopsies (LBX): In February (A), there was lymphohistiocytic portal inflammation, ductal damage (indicated by the orange arrow), and lobular steatosis.

In August (B), persistent mild portal inflammation, ductal damage, prominent ductular reaction (indicated by the orange arrow), and pericholangitis. Nearly two years later (C), the portal tract (indicated by the orange arrow) shows bile duct loss and numerous ceroid/pigmented macrophages (green arrow) at sinusoids.

The three biopsies show a progressive cholestatic injury, supporting an early ductopenic process. The histology can be seen in adverse drug reactions, particularly the effects of the duct loss can persist after this drug is withdrawn.

Although there is a concern for the patient’s Lyme disease, the histologic features associated with Lyme disease are nonspecific and poorly described. Therefore, we are unaware of an association between Lyme disease and ductopenia. Of note, no portal fibrosis is seen in all biopsies.

Citation: Russe JR, Cotton J, Liu L, Maheshwari A. “Vanishing Bile Duct Syndrome (VBDS): How Do Ducts Disappear?” The Liver Meeting: Boston, Massachusetts Nov 10-14, 2023. Hepatology. 2023. (PubMed | Original link that is too big for most browsers)

Related references

Lantos PM, et al. Unorthodox alternative therapies marketed to treat Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2015.

Auwaerter PG. Point: antibiotic therapy is not the answer for patients with persisting symptoms attributable to lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2007.

Melia MT, Auwaerter PG. Time for a Different Approach to Lyme Disease and Long-Term Symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2016. [paper mirror]

Klempner MS, et al. Treatment trials for post-Lyme disease symptoms revisited. Am J Med. 2013.

Lantos PM, Wormser GP. Chronic coinfections in patients diagnosed with chronic lyme disease: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2014.

Steere AC, et al. Lyme borreliosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16090.

Brown JA, et al. Notes from the Field: Reference Laboratory Investigation of Patients with Clinically Diagnosed Lyme Disease and Babesiosis – Indiana, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018.

Rezk, AN, et al. A Case of Doxycycline and Cefuroxime-Induced Liver Injury [abstract]. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015.

Diana Ernst, RPh: Chronic Lyme Diagnosis Leads to Potentially Fatal Drug Reaction