Decades of research have demonstrated with overwhelming evidence that Lyme disease is easily cured with generic antibiotics, even in late stage.

However, some individuals with a history of Lyme disease may have persistent symptoms even after treatment. These symptoms have been called Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS) and usually diminish with time.

Some questioned whether PTLDS is caused by a persistent Lyme disease infection and proposed that long term antibiotics may help such patients.

Patients who received long term antibiotics have zealously evangelized for long-term antibiotic treatment because they believed it helped them.

But, as Dr. Harriet Hall describes in her course on Science-Based Medicine, we humans may believe ineffective treatments work for many reasons:

- The disease may have run its natural course.

- Many diseases are cyclical.

- We are all suggestible.

- The wrong treatment may get the credit.

- Diagnosis and prognosis may be wrong.

- Temporary mood improvement confused with cure

- Psychological needs affect behavior and perceptions

- We confuse correlation with causation

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are experiments that help remove human biases that may influence results. In an RCT, subjects are randomly assigned to either a group receiving a control treatment (usually a placebo) or a group receiving the treatment being tested.

Ideally, the subjects should be blinded so they do not know which treatment they are receiving. The outcomes of the groups are then compared.

As shown below, four American RCTs and two European RCTs all found that long term antibiotics were not meaningfully better for patients than those who received a control treatment (shorter courses or placebo.) These trials also showed that antibiotics can cause severe side effects.

Of course, numerous studies have shown that false Lyme diagnoses are common. Lyme disease was never the cause of the problems in the vast majority of quackery victims who receive a fake “chronic Lyme” diagnosis.

Well-designed RCTs can provide strong evidence regarding drug safety and efficacy. However, because no single study is definitive, it is important to base treatment decisions on multiple studies.

In addition to RCTs, systematic reviews (listed below) all found that long term antibiotics are not warranted for Lyme disease.

In 2024, a systematic review of treatments for post-treatment Lyme disease symptoms (PTLDs) concluded:

Available literature on treatment of PTLDs is heterogeneous, but overall shows evidence of no effect of antibiotics regarding quality of life, depression, cognition and fatigue whilst showing more adverse events. Patients with suspected PTLDs should not be treated with antibiotics.

Besides the lack of efficacy of antibiotics for PTLDs, the review authors noted the reports of adverse events resulting from antibiotic treatment, including hospitalizations and deaths. They were also concerned about antibiotic resistance caused by inappropriate prescribing.

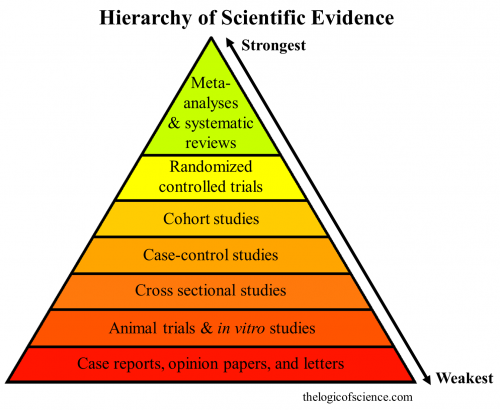

A systematic review is a type of study that summarizes the evidence of multiple studies into one document. A meta-analysis uses statistical methods to compile data from multiple studies into summary measures. These types of studies are considered even stronger evidence than RCTs on the hierarchy of scientific evidence shown below, as explained by The Logic of Science.

Not scientific evidence:

- YouTube and Netflix videos

- Personal anecdotes (“It worked for me!”)

- Gut feelings

- Parental instincts

- some guy you know

- Chronic Lyme support groups

- “Lyme literate” doctors

- Functional and integrative medicine practitioners

- Naturopaths, chiropractors, and homeopaths

- Internet surveys like MyLymeData

- Other red flags of Chronic Lyme quackery

Because they may not apply to humans, studies in animals and in vitro (petri dish or test tube) are among the weaker forms of evidence when determining if a treatment is safe and effective.

Cherry picked evidence may introduce bias. Therefore, case reports and opinion papers are also considered to be weak.

Proponents of fake chronic Lyme diagnoses and treatments frequently use weak evidence (e.g. from animal or petri dish experiments) to justify their beliefs. They also ignore the overwhelming stronger evidence that contradicts their beliefs.

Consensus of experts

In 2010, members of an independent review panel unanimously agreed that the 2006 Lyme disease guidelines produced by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) were medically and scientifically justified. The review panel was certified by an independent ombudsman to be free from conflicts of interest.

Among other things, the review panel concluded:

- In the case of Lyme disease, inherent risks of long-term antibiotic therapy were not justified by clinical benefit.

- To date, there is no convincing biologic evidence for the existence of symptomatic chronic B. burgdorferi infection among patients after receipt of recommended treatment regimens for Lyme disease.

Since 2010, the evidence against long term antibiotics and “chronic Lyme” has become only stronger. In 2020, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, American Academy of Neurology, American College of Rheumatology, representatives from 12 other medical specialties, and patient representatives released comprehensive evidence-based guidelines.

The new guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, American Academy of Neurology, and American College of Rheumatology are consistent with recommendations from medical and scientific organizations around the world.

Experts around the world acknowledge the overwhelming evidence against long-term antibiotics for Lyme disease. Therefore, such treatments can be considered quackery. This is especially true for those who never had Lyme disease in the first place, as is apparent with most victims who receive a “chronic Lyme” diagnosis.

More than placebo?

Based on 6 placebo-controlled trials, we know that longterm antibiotics are not needed for treatment of Lyme disease. However, some patients claim that they feel better while on antibiotics. Are these reports from placebo effects or is something else happening?

Some antibiotic drugs commonly prescribed for Lyme disease—including ceftriaxone (Rocephin) and tetracyclines like doxycycline — have natural anti-inflammatory properties.

For example, one study found that patients who received an injection of ceftriaxone prior to surgery could withstand more pain than similar patients who received either placebo or a different antibiotic.

Because of the pain-relief potential of some antibiotics, feeling better on an antibiotic is therefore not necessarily an indication that the antibiotic had killed harmful bacteria. And if pain relief is required, other anti-inflammatory drugs—like ibuprofen (brand names: Advil, Motrin, Brufen, Nurofen)—are much safer.

Independent Systematic Reviews

The following reviews are in addition to those listed on our scientific consensus page.

Infectious Diseases Society of America, American Academy of Neurology, and American College of Rheumatology: 2020 guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme disease.

UK NICE Guidelines, 2018.

German S3 guideline on Lyme neuroborreliosis, 2018. (English | Deutsch)

Cadavid D, et al. Antibiotics for the neurological complications of Lyme disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016.

Sanchez E, et al. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Lyme Disease, Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, and Babesiosis: A Review. JAMA. [pdf mirror]

Dersch R, et al. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological treatments for acute Lyme neuroborreliosis – a systematic review. Eur J Neurol. 2015.

Dersch R, et al. Treatment of post-treatment Lyme disease symptoms—a systematic review. Eur J Neurol. 2024.

The 6 Negative Randomized Placebo-controlled Trials

The Berende Trial 🇳🇱

Population: “Patients with persistent symptoms attributed to Lyme disease”

280 patients all received intravenous antibiotics (ceftriaxone) for 2 weeks, and then were divided into 3 groups that were to receive different oral treatments for 12 weeks:

- Group 1: Doxycycline

- Group 2: Clarithromycin and hydroxychloroquine

- Group 3: Placebo

Adverse events: “Overall, 205 patients (73.2%) reported at least one adverse event, 9 patients (3.2%) had a serious adverse event, and 19 patients (6.8%) had an adverse event that led to discontinuation of the study drug).” (see table of adverse events)

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the current trial suggests that 14 weeks of antimicrobial therapy does not provide clinical benefit beyond that with shorter-term treatment among patients who present with fatigue or musculoskeletal, neuropsychological, or cognitive disorders that are temporally related to prior Lyme disease or accompanied by positive B. burgdorferi serologic findings.

A later analysis of the study data found that long-term antibiotics did not improve cognitive performance.

Berende publications

Berende A, et al. Randomized Trial of Longer-Term Therapy for Symptoms Attributed to Lyme Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1209-20. [Persistent Lyme Empiric Antibiotic Study Europe (PLEASE)]

Berende A, et al. Effect of prolonged antibiotic treatment on cognition in patients with Lyme borreliosis. Neurology. 2019;

Berende, A. Dissertation: Persistent symptoms attributed to Lyme disease and their antibiotic treatment. Results from the PLEASE study. 2019.

Berende A, et al. Cognitive impairments in patients with persistent symptoms attributed to Lyme disease. BMC Infect Dis. 2019.

van Middendorp H, et al. Expectancies as predictors of symptom improvement after antimicrobial therapy for persistent symptoms attributed to Lyme disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2021.

Stelma FF, et al. Classical Borrelia Serology Does Not Aid in the Diagnosis of Persistent Symptoms Attributed to Lyme Borreliosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Life (Basel). 2023.

Berende A, et al. Persistent Lyme Empiric Antibiotic Study Europe (PLEASE)–design of a randomized controlled trial of prolonged antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms attributed to Lyme borreliosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014.

Commentary on the Berende trial

- Neurology Today: Prolonged Antibiotics Do Not Improve Neurocognitive Outcomes in Persistent Lyme Disease

- Science-Based Medicine: Chronic Lyme Disease – Another Negative Study

- Medscape: Lyme Disease Syndrome: Longer Antibiotics May Not Help

- Forbes: Long-Term Antibiotic Use For Lyme Disease Doesn’t Work, Study Finds

- American Lyme Disease Foundation comment: Is There a Need to Conduct Still More Clinical Trials on the Benefit of Extended Antibiotic Therapy for the Treatment of Persistent Post-treatment Symptoms of Lyme Disease?

The Fallon Trial 🇺🇸

Population: Patients with “well-documented Lyme disease, with at least 3 weeks of prior IV antibiotics, current positive IgG Western blot, and objective memory impairment.”

Fallon BA, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of repeated IV antibiotic therapy for Lyme encephalopathy. Neurology. 2008;70(13):992-1003. (paper mirror)

Commentary on the Fallon trial:

Neurology Today: New Study Reports Short-term Benefits But Not Sustained Improvement in Cognition With Prolonged Antibiotic Use for Lyme Disease Encephalopathy

Halperin JJ. Prolonged Lyme disease treatment: enough is enough. Neurology. 2008

Marques A, et al. Comments on the Fallon study. Neurology. 2008.

The Oksi Trial 🇫🇮

Population: “Patients with disseminated Lyme borreliosis”

Both groups received an initial treatment of intravenous CRO 2 g daily for 3 weeks, followed by the randomized drug or PBO.

Oksi J, et al. Duration of antibiotic treatment in disseminated Lyme borreliosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26(8):571-81. (Shareable link)

The Krupp Trial 🇺🇸

Population: “Patients with Lyme disease with persistent severe fatigue at least 6 or more months after antibiotic therapy”

Krupp LB, et al. Study and treatment of post Lyme disease (STOP-LD): a randomized double masked clinical trial. Neurology. 2003;60(12):1923-30.

Commentary on the Krupp trial

- American Academy of Neurology: Still no effective treatment for post-Lyme disease symptoms

- Jwatch: Medicating Lyme Disease Before It Starts and After It Ends

- Jwatch: More Studies on Prolonged Antibiotic Therapy for Chronic Lyme Disease, 2003

- Steiner I. Treating post Lyme disease: trying to solve one equation with too many unknowns. Neurology. 2003.

The Two Klempner Trials 🇺🇸

Two trials published together

Population for trial 1: People treated for Lyme disease with persistent symptoms who tested positive for IgG antibodies

Population for trial 2: People treated for Lyme disease with persistent symptoms who tested negative for IgG antibodies

Klempner MS, et al. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):85-92.

Further analysis:

Kaplan RF, et al. Cognitive function in post-treatment Lyme disease: do additional antibiotics help? Neurology. 2003;60(12):1916-22.

Klempner MS. Controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with post-treatment chronic Lyme disease. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2002.

Other studies

A number of additional studies support the scientific consensus that long term antibiotics for Lyme disease are not justified.

Randomized controlled trials

A 2005 RCT by Dattwyler and colleagues randomized patients with late Lyme disease to receive either 14 days of intravenous antibiotics (n=80) or 28 days of intravenous antibiotics (n=63). There were 5 treatment failures in the 14 day group and 0 treatment failures in the 28 day group.

A small 2012 cross-over trial included 15 people with persistent symptoms at least 6 months after treatment for neuroborreliosis (NB). In the study, subjects were randomized between two 3-week treatment groups: doxycycline or placebo. After 6 weeks, the subjects “crossed over” to the other group. The authors concluded, “doxycycline-treatment did not lead to any improvement of either the persistent symptoms or quality of life in post-NB patients.”

A 2022 European RCT by Solheim and colleagues found that two weeks of doxycycline worked just as well as six weeks for early neuroborreliosis.

Studies of post-antibiotic Lyme arthritis

Note: Post-antibiotic Lyme arthritis is not the same as post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS)

A 1999 study by Carlson and colleagues found no evidence of Borrelia Burgdorferi DNA in knee tissue samples from 26 patients with post-antibiotic Lyme arthritis.

A 2019 study by Dr. Brandon Jutras, Dr. Robert Lochhead, and others found that part of bacteria cell wall called peptidoglycan may trigger an inflammatory reaction that results in persistent Lyme arthritis.

Also in 2019, Grillon and other researchers from France found post-antibiotic Lyme arthritis could be cured using DMARDs.

Citations

Dattwyler RJ, et al. A comparison of two treatment regimens of ceftriaxone in late Lyme disease. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005. (Shareable link)

Carlson D, et al. Lack of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA in synovial samples from patients with antibiotic treatment-resistant Lyme arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999.

Jutras BL, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi peptidoglycan is a persistent antigen in patients with Lyme arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019.

Grillon A, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes after treatment of a national cohort of PCR-positive Lyme arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019. [accepted manuscript]

jöwall J, et al. Doxycycline-mediated effects on persistent symptoms and systemic cytokine responses post-neuroborreliosis: a randomized, prospective, cross-over study. BMC Infect Dis. 2012.

Solheim AM, et al. Six versus 2 weeks treatment with doxycycline in European Lyme neuroborreliosis: a multicentre, non-inferiority, double-blinded, randomised and placebo-controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022.

Discussion by scientists

NIH: Lyme Disease Antibiotic Treatment Research

NIH: Chronic Lyme Disease

NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health: Lyme Disease

CDC: Dangers of long-term or alternative treatments for Lyme disease

CDC: Alternative treatments for Lyme disease

Very useful analysis: Klempner MS, et al. Treatment trials for post-Lyme disease symptoms revisited. Am J Med. 2013.

Klempner MS, et al. The reply. Am J Med. 2014.

Marques A. Persistent Symptoms After Treatment of Lyme Disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2022.

Auwaerter PG. Point: Antibiotic therapy is not the answer for patients with persisting symptoms attributable to lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2007.

Melia MT, Auwaerter PG. Time for a Different Approach to Lyme Disease and Long-Term Symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2016. [paper mirror]

Oliveira CR, Shapiro ED. Update on persistent symptoms associated with Lyme disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015. [video commentary]

Wong KH, et al. A Review of Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome and Chronic Lyme Disease for the Practicing Immunologist. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2022. (shareable link)

Steere AC. Posttreatment Lyme disease syndromes: distinct pathogenesis caused by maladaptive host responses. J Clin Invest. 2020.

Verschoor YL, et al. Persistent Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato Infection after Antibiotic Treatment: Systematic Overview and Appraisal of the Current Evidence from Experimental Animal Models. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2022.

Klempner MS, et al. Lyme borreliosis: the challenge of accuracy. Neth J Med. 2012.

Scott Gavura at Science-based Medicine: Avoid prolonged antibiotics for “Chronic Lyme”

See statements from medical societies in our Scientific Consensus section.

Updated August 15, 2024