Dr. Jonathan Howard, MD is a neurologist who is dedicated to improving the practice of medicine. He is the author of Cognitive Errors and Diagnostic Mistakes: A Case-Based Guide to Critical Thinking in Medicine.

The book is available through the publisher and major book sellers such as Amazon.

Dr. Harriet Hall of Science-based Medicine wrote a glowing review of the book and recommended it for doctors and everyone else:

As the book explains, “The brain is a self-affirming spin-doctor with a bottomless bag of tricks…” Our brains are “pattern-seeking machines that fill in the gaps in our perception and knowledge consistent with our expectations, beliefs, and wishes”. This book is a textbook explaining our cognitive errors. Its theme is medicine but the same errors occur everywhere.

We all need to understand our psychological foibles in order to think clearly about every aspect of our lives and to make the best decisions. Every doctor would benefit from reading this book, and I wish it could be required reading in medical schools. I wish everyone who considers trying CAM would read it first. I wish patients would ask doctors to explain why they ordered a test.

Below are excerpts from the book that discuss three major aspects of human psychology that may cause us to believe we have conditions we don’t have: motivated reasoning, Forer effect, and availability heuristic.

Motivated Reasoning

Confirmation bias leads people not only to seek out information that confirms a preexisting belief, but also to interpret information in a way that is favorable to their preconceived viewpoints. Information that supports a belief will be readily accepted, a form of confirmation bias called motivated reasoning.

Motivated reasoning is well illustrated by the following parable:

A conspiracy theorist dies and goes to heaven. When he arrives at the pearly gates, God is there to receive him.

“Welcome. You are permitted to ask me one question, which I will answer truthfully.”

Without hesitating, the conspiracy theorist asks, “Was the moon landing fake?”

God replies, “No, the moon landing was real. NASA astronauts walked on the moon in 1969.”

The man thinks to himself, “This conspiracy goes even deeper than I thought.”

Motivated reasoning is an emotional mechanism that allows people to avoid uncomfortable cognitive dissonance and permits them to hold implausible ideas, such as that Bigfoot exists, or scientifically refuted ones, such as that vaccines cause autism.

Motivated reasoning is most likely to occur with longstanding beliefs that have a strong emotional component and with beliefs that have been declared publicly. With such core beliefs, little effort is spared to discredit contradictory information and avoid unpleasant cognitive dissonance. We might like to think that we base our beliefs on the facts. However, just as often, our willingness to accept facts is based on our beliefs.

I witnessed a fascinating example of such motivated reasoning during my residency. One weekend when I was working in the hospital, I received a message that there was a support group for patients suffering from chronic Lyme disease, a medically dubious diagnosis.

I had no particular interest in going, but there were sandwiches, so I ran there as fast as I could. It was fascinating to hear multiple patients describe how they had taken ten negative tests for Lyme disease before one finally came back positive.

In their minds, the ten negative tests were wrong, while the one positive test was correct. In other words, they knew they had Lyme disease and were going to keep testing themselves for it until they got the diagnosis they were already certain they had.

I similarly encountered patients who have gone to multiple doctors, a practice called doctor-shopping, searching for one who will give them diagnosis they already “know” they have. These patients are certain they have multiple sclerosis (MS) and will search until they find a doctor who confirms this.

Forer Effect

Case

Evie was a 45-year-old woman who presented with a panoply of symptoms, which included fatigue, weight gain, “brain fog,” decreased libido, loss of energy, difficulty falling asleep, joint pains, poor concentration, and anxiety. She had seen multiple different clinicians who had ordered a large number of tests and images, none of which had revealed the cause of her symptoms.

A friend of hers suggested she take an online test for “adrenal fatigue,” [a condition not recognized by medical science]. She found that she had “nearly every symptom.” She contacted the clinician who designed the test, and the clinician confirmed the diagnosis after an in-person consultation.

What Dr. Grater Was Thinking

Adrenal fatigue is both common and undiagnosed. I had reviewed the results of Evie’s survey prior to her arrival. She matched most of the symptoms perfectly. Of course, I ruled out common mimics of adrenal fatigue, such as thyroid disorders and low vitamin B12.

Once Evie’s blood work came back normal, the diagnosis was pretty clear. We worked hard on minimizing stress in her life, making sure she got enough sleep and exercise. We made a lot of changes to her diet and started her on rosemary essential oils, vitamin supplementation, magnesium, and adaptogenic herbs such as ashwagandha, rhodiola rosea, schisandra, and holy basil. Within two months she was feeling much better.

Discussion

The Forer effect is a psychological phenomenon in which people feel that vague, nonspecific descriptions of their personality are, in fact, highly specific to them. These statements are called “Barnum statements” after the circus entertainer P. T. Barnum, who reportedly said that “we have something for everybody.”

The Forer effect is named after the psychologist Bertram Forer, who gave his students a test called the “Diagnostic Interest Blank”. They were then given a supposedly personalized description of their personality and asked to rate how well it described them. It consisted of the following 12 descriptors:

- You have a great need for other people to like and admire you.

- You have a tendency to be critical of yourself.

- You have a great deal of unused capacity, which you have not turned to your advantage.

- While you have some personality weaknesses, you are generally able to compensate for them.

- Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside.

- At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing.

- You prefer a certain amount of change and variety and become dissatisfied when hemmed in by restrictions and limitations.

- You pride yourself as an independent thinker and do not accept others’ statements without satisfactory proof.

- You have found it unwise to be too frank in revealing yourself to others.

- At times you are extroverted, affable, sociable, while at other times you are introverted, wary, reserved.

- Some of your aspirations tend to be pretty unrealistic.

- Security is one of your major goals in life.

Unbeknownst to the students, these items were taken from the astrology section of a newspaper, and each person received the same list. Despite this, most students felt it applied to them very well, rating it a 4.26 out of 5.

Many others have repeated Forer’s initial experiment, and the results have been very similar in their studies. The journalist John Stossel has an amusing video where a group of people receive a horoscope that was supposedly selected specifically for them based on their birthdate and birthplace and prepared by a qualified astrologer. They were amazed at how well it described their personality, until the truth is revealed—it was actually based on the horoscope of a serial killer.

The Forer effect exists because Barnum statements are highly generalized, but people perceive them to be highly specific and unique to them. People are eager to take vague statements and apply them to their own lives, especially when the statements are positive, felt to be specifically for them, and provided to them by a trusted source. As philosopher Robert T. Carroll wrote:

People tend to accept claims about themselves in proportion to their desire that the claims be true rather than in proportion to the empirical accuracy of the claims as measured by some non-subjective standard. We tend to accept questionable, even false statements about ourselves, if we deem them positive or flattering enough.

The Forer effect largely explains the ability of psychics, fortune tellers, horoscopes, and online personality tests to convince people something unique about them is being revealed, when in fact they are only receiving vague, generic statements about their life and personality. Many psychics employ a technique called cold reading, in which the psychic makes general statements that can apply to almost everyone.

For example, I predict that you, the reader, are an open-minded person who is willing to consider an idea, but may quickly become impatient with sloppy, lazy thinking. (The trick of describing a person with one personality trait, and its opposite, is called the “rainbow ruse”). I predict you sometimes have spent a large sum of money on something you didn’t need. I predict you generally like your job, but sometimes wonder if it’s really what you want to do for the rest of your life.

The Forer effect is so powerful that there are even some instances where initially skeptical people convinced themselves they had genuine psychic abilities because of the positive response they received after providing people with vague statements such as these.

When applied to medicine, the Forer effect is a form of the selection bias where patients fill out a survey (often online), and indeed discover they have the condition tested by the survey.

To see how this might work, let’s consider a very prevalent and serious condition known as Howard’s Syndrome (HS). It occurs in people who don’t eat donuts every day. If you have at least four of the following symptoms, you may suffer from HS!

- You don’t have as much energy as you used to. You often feel “run down.”

- You cannot exercise as vigorously as in the past.

- You have trouble losing weight.

- At times, you have trouble falling asleep. At other times, you wake up too early and have trouble falling back asleep.

- You sometimes get a dull headache or pain in your lower back.

- Certain foods upset your stomach.

- Sometimes you feel sad, anxious, or irritable for no particular reason.

- You have unexplained muscle and joint pains.

- Your sex drive is not the same as it was when you were younger.

- Your vision is not as sharp as it used to be.

How well do these descriptions fit you? I imagine if you gave this list of symptoms to a group of busy adults, most would check off at least a few symptoms, and some would check of most of them. Voila! They have HS and must rush to the bakery to eat as many gluten-laden donuts as possible. However, like the vague personality statements in the Forer effect, seemingly specific symptoms are actually vague and general.

Though they are likely unaware of doing so, some clinicians employ a version of the Forer effect to convince people that they have diseases of dubious validity. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioners are particularly noted to employ this method. As I did with HS, they use vague symptom “checklists” and online questionnaires that could apply to many people coping with the aches and pain of normal aging and the stressors of the modern world.

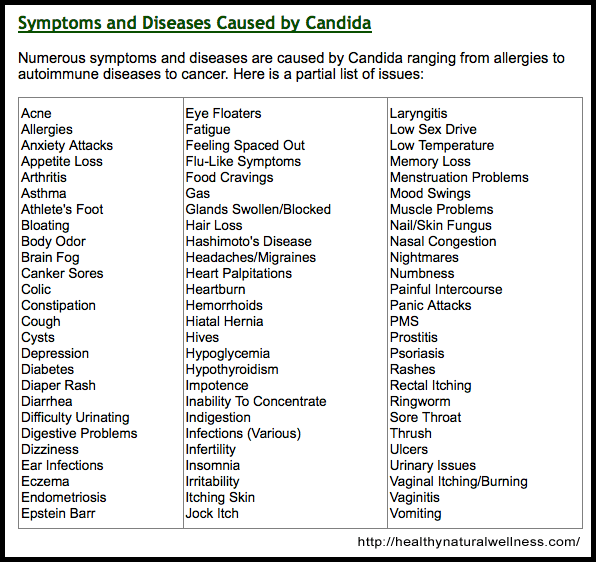

Consider, for example, the following list from the website healthynaturalwellness.com, which proposes that Candida infections are responsible for a large panoply of symptoms affecting multiple organ systems. (Not surprisingly, they also seem to be selling the cure in the form of probiotics).

Almost identical symptom checklists can be found for chronic Lyme disease, multiple chemical sensitivity, adrenal fatigue, bartonella infections, leaky gut syndrome, gluten intolerance, fluoride toxicity, and perceived injuries from vaccines. Articles such as “10 Signs You Have a Leaky Gut—and How to Heal It” abound on the internet. I suspect that if only the name of the disease being discussed were changed from leaky gut syndrome to gluten sensitivity, the article would work just as well.

These checklists and articles are most likely to be encountered by frustrated people with undefined illnesses for whom mainstream medicine has offered no diagnosis or treatment. As such, finding a checklist that explains their symptoms and provides a diagnostic label is likely to be very reassuring.

In questioning the existence of these diagnoses, I am by no means minimizing the suffering of the patients who have been diagnosed with these disorders. However, these diagnoses are essentially unfalsifiable, meaning there is no way to rule them out.

What test could be performed to definitively tell a person they don’t have leaky gut syndrome, adrenal fatigue, or gluten sensitivity? Even when tests exist, such as for Lyme disease, CAM practitioners often claim those tests are insensitive, and instead use unvalidated tests performed by unaccredited laboratories.

Patients are likely not the only ones fooled by these checklists. The existence of questionable diseases is reinforced for the CAM practitioner who routinely encounters people whose symptoms are largely matched by their checklist. In this way, they are like a phony psychic who inadvertently becomes convinced of his own powers after consistently receiving positive feedback from his readings.

It is undeniably true that similar symptom checklists exist for diseases of unquestioned validity, such as multiple sclerosis (MS). Consistent with the Forer effect, many patients convince themselves they have the disease after reading these lists online.

It is quite common for patients to come to my office certain they have MS as they have “every symptom.” However, unlike the conditions theorized by CAM practitioners, responsible clinicians do not create these lists to suggest the diagnosis to potential patients. Moreover, MS can almost always be definitively ruled out with imaging and a spinal tap, though even when these results are normal, some patients continue to insist they have the disease.

The Forer effect also explains the value of asking open-ended questions while taking a patient’s history. A simple request that patients describe their symptoms, combined with thoughtful, targeted follow-up questions, is most likely to yield accurate information. In contrast, leading questions may suggest symptoms to the patient. Like those who marvel at the accuracy of their horoscope, patients may feel that a clinician’s leading questions are specifically for them, yielding false positive results.

Conclusion

The Forer effect uses vague, nonspecific statements to convince people that a specific truth about them is being revealed. When given vague statements, especially positive ones that are perceived as specifically for them, people easily connect these statements to their life. Psychics use the Forer effect to produce cold readings, convincing people they know amazing details of their lives, when in fact they know only platitudes that apply to most of us in one way or another.

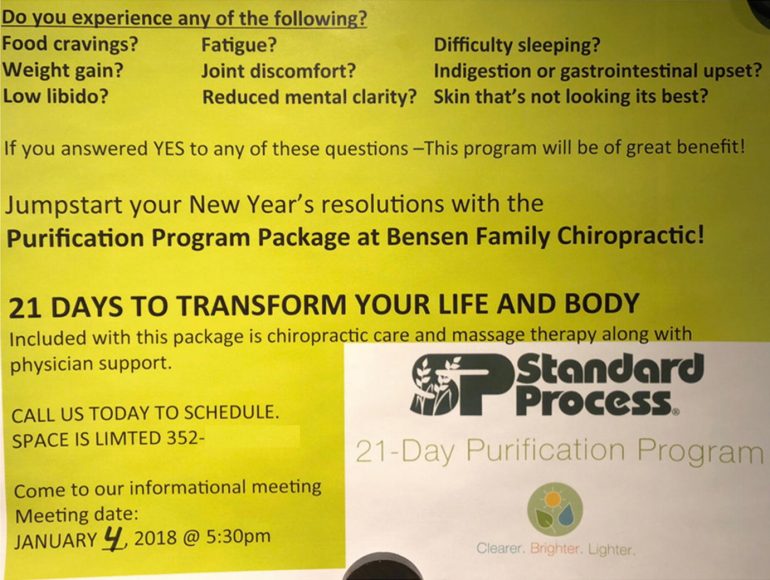

In medicine, online symptoms checklists are commonly employed by CAM practitioners. This technique replicates the cognitive trick of the Forer effect. People with multiple symptoms that lack a unifying diagnosis may easily be made to feel that their correct diagnosis has been miraculously revealed. Similarly, CAM practitioners may genuinely come to believe their diagnostic criteria can reveal diagnoses that eluded their close-minded, conventional colleagues (Fig. 9.1).

Fig. 9.1 Marketing a purification package using the Forer effect. (Standard Process. 2018. Advertising flyer distributed at various locations [Personal image].)

However, no responsible clinician solicits prospective patients with a long laundry list of vague, common symptoms only to invariably diagnosis them with the “disease” they treat based on their responses. Rather, clinicians should ask patients what symptoms they have, order appropriate diagnostic tests, and render a diagnosis in combination with the history, exam, and supportive evidence.

Availability Heuristic

Case

Adam was 28-year-old man who presented to the ER with a headache of 24 hours duration. The headache was described as “throbbing” and was mostly over his right eye. He had some mild nausea and photophobia. He appeared uncomfortable, but otherwise had a normal examination.

A non-contrast head CT was normal and a neurology consult was called to advise the ER on treating a migraine. The neurologist insisted on an MR venogram to rule-out sinus venous thrombosis, a serious but uncommon condition where there are blots clots in the venous system of the brain. The neurologist continued this pattern of ordering MR venograms the next month until the head of the neuroradiology department admonished the neurologist for his overuse of the test.

What Dr. Gang Was Thinking

A doctor I know used to joke, “I’m guided by my decades of clinical experience, especially my last case.” That is a perfect example of what happened to me. Several weeks before Adam arrived, we had a morbidity and mortality conference about a young woman who presented with a “migraine.” She was sent home from the ER, only to return the next day with a seizure and frontal lobe hemorrhage. Only then was she diagnosed with sinus venous thrombosis.

The ER doctor who sent her home felt horrible, and the patient ended up not doing well. This case was certainly on my mind every time I saw a patient with a headache after that. The only way to definitively rule out sinus venous thrombosis is an MR venogram or a similar imaging test. In retrospect it was not an appropriate test to order on every patient with a headache, and to be honest, I was unaware that I was doing this until it was brought to my attention.

Case

Lucas was a 28-year-old homeless man who was found unconscious in an abandoned house, with two people by his side, one of whom was dead, the other of whom was also unconscious. On examination, Lucas was obtunded, responding only to painful stimuli.

He was given both naloxone and flumazenil, which are antidotes to poisoning by opiates and a class of sedatives called benzodiapines (medications such as ValiumTM and XanaxTM). He was given several repeat doses when he failed to improve.

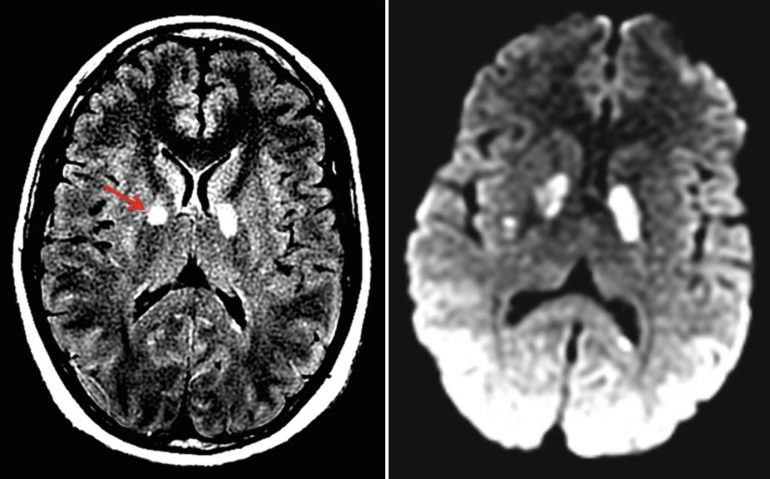

An MRI done the next day revealed bright lesions in a deep structure of the brain known as the globus pallidus consistent with carbon monoxide poisoning. When the police went back to the house, a space heater was found in a poorly ventilated room (Fig. 23.6).

Fig. 23.6 FLAIR and diffusion-weighted MRIs showing hyperintensity in the globus pallidus, due to carbon monoxide poisoning (red arrow)

What Dr. Mehta Was Thinking

There had been several cases at our hospital of patients with severe opiate overdoses, and many more cases in the news of people who never made it to the hospital because they had died. These were amplified in the media after the deaths of celebrities such as Philip Seymour Hoffman and Prince. As such, when Lucas and his companions arrived in the ER, I was primed to treat them as overdose cases. This was not a bad thing on its own.

Heroin overdoses were common, they are obviously dangerous, and they are treatable. The respiratory depression caused by heroin can be multiplied when combined with alcohol or benzos like ValiumTM or XanaxTM. However, in my haste and eagerness to treat him for the overdose, which I was sure he had, I neglected to take a step back and think what else this could be.

Had Lucas and his friends been someone who didn’t fit my stereotype of a drug user—an older person or a clergyman, for example—I likely would have considered other causes of their presentation. Similarly, had the news and my e-mail not been full of warning about the crisis of opiate overdoses, I almost certainly would have considered an overdose as my top differential, but not to the exclusion of other conditions.

It is important to remember that just because a condition is in the news, this does not mean other conditions don’t exist. Ironically, after word of this case spread throughout the hospital, the next dozen or so patients with similar presentations were all evaluated for having carbon monoxide poisoning.

Discussion

The availability heuristic is the tendency to judge things as being more likely, or frequently occurring, if they readily come to mind. It was coined by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman who explained the heuristic by saying, “If you can think of it, it must be important”. They performed a simple experiment to demonstrate the availability heuristic.

They asked subjects the following question: “If a random word is taken from an English text, is it more likely that the word starts with a K, or that K is the third letter?” It is relatively easy to think of words that begin with K, compared to those that have K in the third position. As a result, subjects underestimated the number of words that have K as the third letter, despite the fact that there are more than three times as many such words (Fig. 23.7).

Fig.23.7 As a consequence of the availability bias, what we think is influenced by what we can recall. (source: I f-ing hate pseudoscience.)

The availability heuristic also causes people to dramatically over or under estimate various risks based on how frequently they occur in the media. Deaths by extremely rare but dramatic events, such as Ebola, may cause a great panic, whereas deaths from causes perceived as mundane and common, such as influenza or traffic accidents, do not generate either the same headlines or concerns. Prominent media coverage of crimes may lead people to think that the crime rate is higher than it has been in the past, even when the crime rate is at a historic low.

People can behave in incredibly illogical ways as a result of the availability bias. For example, from 2005 to 2015 jihadists killed 94 people in the US, while 301,797 people were killed with guns during this time [source]. Despite this, a 2016 survey of 1,500 Americans found that terrorist attacks were the second most common fear after “corruption of government officials”.

In one sense this is not entirely irrational. After all, terrorists may kill thousands of people in one year and none the next (in statistics, such risks are called long-tailed). In contrast, deaths from accidents and diseases are unlikely to fluctuate greatly from year to year (infectious diseases being an important exception to this generalization). Moreover, deaths from terrorist attacks may be low precisely because our fear leads us to protect ourselves against them.

However, because of the availability bias, what people fear the most often reflects what the media reports, not what is actually dangerous to them. As Max Bazerman, a business professor, said, “We over-react to visible threats. When there is someone out to get you, it is more visible than when you are silently dying in a hospital.”

When the availability bias affects risk assessment, people can die. For example, Gerd Gigerenzer, a risk specialist, estimated that an extra 1,595 Americans died in car accidents in the year after the 9/11 terrorist attacks because they chose to drive rather than fly.

Our minds naturally filter information that has relevance to us, weeding out seemingly extraneous information. The availability heuristic is similar to a psychological phenomenon known as the frequency illusion (also known as the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon), which occurs when people who learn or notice something novel begin to see it everywhere.

For example, if someone buys a new red car, they may start to see that same car wherever they go. While these cars were always there, they previously lacked emotional salience and so went unnoticed. In medicine, recent exposure to a disease, especially in a personal or emotional way, will increase the likelihood of it being considered. Conversely, if a disease has not been encountered, its availability diminishes, and it may be underdiagnosed.

It is only natural that exposure to a disease, either personally or in the media, will increase awareness of it. This is often appropriate, as many conditions do occur in clusters. Clinicians should be aware of outbreaks of infectious diseases or drug epidemics in their area of practice. However, it becomes potentially harmful when other, less available diseases are not considered or when the probability of a certain diagnosis is inappropriately inflated because it was recently seen.

At times, a rare diagnosis or bad outcome can garner significant attention within a hospital, affecting the behavior of everyone who learns about it. If a woman presents with confusion and is found to have Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), it is likely that her case will be widely discussed and trainees will be brought in to meet her. As a result, this literally one-in-a-million diagnosis may lead the next several patients who present with confusion to be tested for CJD. Obviously, that a rare diagnosis is identified in a particular hospital does not mean the prevalence of that disease has then increased.

Henk Schmidt and colleagues conducted a study demonstrating evidence of the availability heuristic in medicine. In their study, 38 internal medicine residents read a Wikipedia entry about one of two diseases. In a seemingly unrelated study, they were later given eight cases, two that superficially resembled the disease they had read about, two that resembled the other disease they did not read about, and four filler cases. Their diagnostic accuracy was lowest on the two cases that resembled the disease they read about in Wikipedia, showing the impact of the availability heuristic.

I suspect that specialists in particular may be prone to the availability bias. By definition, they see only a small number of conditions and, as such, may be especially prone to diagnose the conditions they treat. One hip specialist told my mother that she had trochanteric bursitis and explained his conclusion in part by telling her “I see it all the time.”

I also suspect that many complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioners are highly vulnerable to the availability bias. Many CAM practitioners have a small number of go-to explanations as the cause for a diverse range of symptoms. Consider the case of “Lyme literate” clinicians. Such clinicians embrace the concept of chronic Lyme disease, a diagnosis rejected by mainstream medical practitioners. Such clinicians use tests whose sensitivity and specificity have never been validated, believing that “the standard recommended tests… miss 80–90% of cases” [source].

Even when the tests are negative, some clinicians believe that “over time, doctors who see a lot of Lyme patients can consistently pick them out from other fatiguing conditions by just reviewing the patient’s history and review of systems (signs and symptoms).”

Many “checklists” have been used to screen for chronic Lyme disease. Looking at these lists, it can be hard to think of a symptom that is not present. Moreover, I am sure that many otherwise healthy people have several of these symptoms. Who doesn’t feel forgetful from time to time or have a headache or trouble sleeping?

A typical “chronic Lyme disease” checklist is below. How many symptoms do you have?

Head, Face, Neck:

Headache

Facial paralysis (like Bell’s palsy) Tingling of nose, cheek, or face Stiff neck

Sore throat, swollen glands

Heightened allergic sensitivities

Twitching of facial/other muscles Jaw pain/stiffness (like TMJ)

Change in smell, taste

Digestive/excretory System:

Upset stomach (nausea, vomiting)

Irritable bladder

Unexplained weight loss or gain

Loss of appetite, anorexia

Respiratory/Circulatory Systems:

Difficulty breathing

Night sweats or unexplained chills

Heart palpitations

Diminished exercise tolerance Heart block, murmur

Chest pain or rib soreness

Psychiatric Symptoms:

Mood swings, irritability, agitation

Depression and anxiety

Personality changes

Malaise

Aggressive behavior / impulsiveness

Suicidal thoughts (rare cases of suicide) Overemotional reactions, crying easily Disturbed sleep: too much, too little, difficulty falling or staying asleep

Suspiciousness, paranoia, hallucinations

Feeling as though you are losing your mind Obsessive-compulsive behavior

Bipolar disorder/manic behavior Schizophrenic-like state, including hallucinations

Cognitive Symptoms:

Dementia

Forgetfulness, memory loss (short or long term)

Poor school or work performance

Attention deficit problems, distractibility

Confusion, difficulty thinking

Difficulty with concentration, reading, spelling

Disorientation: getting or feeling lost

Reproduction and Sexuality:

Females:

Unexplained menstrual pain, irregularity

Reproduction problems, miscarriage, stillbirth,

premature birth, neonatal

Death, congenital Lyme disease

Extreme PMS symptoms

Males:

Testicular or pelvic pain

Eye, Vision:

Double or blurry vision, vision changes Wandering or lazy eye

Conjunctivitis (pink eye) Oversensitivity to light

Eye pain or swelling around eyes Floaters/spots in the line of sight

Red eyes

Ears/Hearing:

Decreased hearing

Ringing or buzzing in ears

Sound sensitivity

Pain in ears

Musculoskeletal System:

Joint pain, swelling, or stiffness

Shifting joint pains

Muscle pain or cramps

Poor muscle coordination, loss of reflexes Loss of muscle tone, muscle weakness

Neurologic System:

Numbness in body, tingling, pinpricks Burning/stabbing sensations in the body Burning in feet

Weakness or paralysis of limbs

Tremors or unexplained shaking Seizures, stroke

Poor balance, dizziness, difficulty walking Increased motion sickness, wooziness Lightheadedness, fainting Encephalopathy (cognitive impairment from brain involvement)

Encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) Meningitis (inflammation of the protective membrane around the brain) Encephalomyelitis (inflammation of the brain and spinal cord)

Academic or vocational decline

Difficulty with multitasking

Difficulty with organization and planning Auditory processing problems

Word finding problems

Slowed speed of processing

Skin Problems:

Benign tumor-like nodules Erethyma Migrans (rash)

General Well-being:

Decreased interest in play (children) Extreme fatigue, tiredness, exhaustion Unexplained fevers (high or low grade) Flu-like symptoms (early in the illness) Symptoms seem to change, come and go

Other Organ Problems:

Dysfunction of the thyroid (under or over active thyroid glands)

Liver inflammation

Bladder & Kidney problems (including bed wetting)

(Source: “What is lyme disease?“, Caravan Sonnet.)

According to Caravan Sonnet, an author who is active in the Lyme community:

The symptoms of Lyme Disease vary but most people struggle from many of the following symptoms: debilitating fatigue, heart issues, heart palpitations, arthritis, facial numbness, blood pressure problems, extreme pain, autoimmune disorders, malnutrition, hair loss, vision problems, skin issues, rashes, panic attacks, adrenal failure (or fatigue), memory issues, food allergies, unexplained allergic reactions, insomnia, inability to absorb vitamins and nutrition, hormonal issues, circulation issues, dizziness, seizures, body numbness, blindness, migraines, paralysis in extremities, heart attacks, inability to handle temperature change, lung function, shortness of breath, menstrual issues, and the list goes on and on and on. I have just listed a few but here are hundreds more.

Moreover, Lyme disease is said to mimic multiple other diseases. As Ms. Sonnet explains:

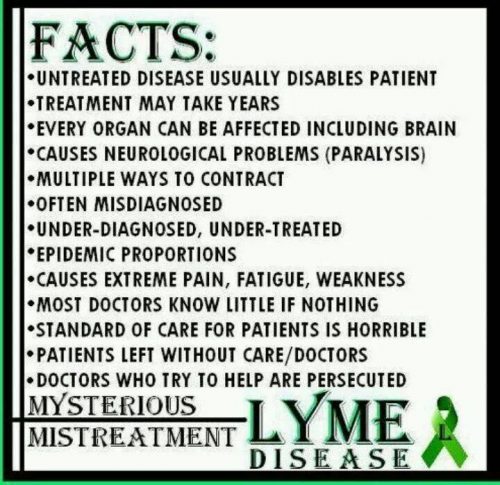

Lyme is considered the “Great Imitator” and is known to imitate over four hundred different diseases including CFS/ME (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome), Fibromyalgia, IBS, Lupus, MS, Autoimmune Disorders, Alzheimer’s, ALS, Migraines, Depression, Meningitis, Lou Gehrig’s Disease, and hundreds of others. (Fig. 23.9)

Fig. 23.9 A meme from a Lyme disease awareness page

I have often wondered what would happen if 100 healthy people went to a “Lyme literate” clinician. I suspect that many of them, suffering only the aches, pains, and fatigue of aging and everyday life, would be diagnosed with chronic Lyme disease as it is the main, and possibly only diagnosis available to these clinicians. The consequences of this are especially important given that patients diagnosed with chronic Lyme disease are treated with antibiotics for months or even years, despite studies showing that this is ineffective.

The availability heuristic can also impair the perception of a treatment’s risks and benefits. If a clinician has had success or failure with a treatment, it is likely to influence their future use of this treatment, even though their particular experience is unlikely to impact its overall risks/benefit ratio.

In my own practice, I routinely use a medication that can rarely cause significant infections, even leading to death. After I cared for a patient with such an infection, I became much more conservative with my use of this medication. Objectively, this makes no sense.

Yes, I treated a patient who experienced a bad outcome with this treatment. However, my individual experience should not dissuade me from its use any more than if I had read about this bad outcome happening to a patient on a different continent. The risks and benefits of this medication did not change just because I happened to personally witness a bad outcome.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware that their experience is distorted by recent or memorable, the experiences of their colleagues, and the news. While it is not possible to control what comes to one’s mind, clinicians should strive to approach each case as an independent entity, likely completely unrelated to the ones that came before.

As Mark Crislip, an infectious disease specialist, said, the three most dangerous words in medicine are “in my experience”. Similarly, clinicians should know that a good or bad outcome with a treatment while under that clinician’s care does not affect the overall risk/benefit profile of that treatment.